Episode 143

Theaster Gates on Building and Bridging Culture, From Chicago to Japan

Over the past two decades, the artist Theaster Gates has poured himself into his multifaceted art practice that spans pottery, painting, sculpture, urban development, performance, archival research, and arts administration. Throughout much of that time, he has also held various roles at the University of Chicago, where today he’s a visual arts professor and director of the university’s Arts + Public Life initiative. Along the way, he has risen to become one of the most widely celebrated figures in the world of art, transforming abandoned, dormant buildings in Chicago’s Grand Crossing neighborhood, on the city’s South Side, into dynamic third spaces for social, cultural, and spiritual communion through his nonprofit Rebuild Foundation; linking Chicago, where he was born and raised and is based, with Japan, where in 2004 he trained with master potters in the coastal city of Tokoname and has maintained a deep connection ever since (his profound Chicago-Japan ties were exemplified in last year’s “Afro-Mingei” solo exhibition at Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum); and effectively rescuing, recontextualizing, and resuscitating important archives, whether that of the Johnson Publishing Company, which published Ebony and Jet magazines; glass lantern slides from the University of Chicago’s art history department; or notable record collections, from those of the Chicago D.J. Frankie Knuckles to the Olympic track and field star Jesse Owens.

In a certain sense, Gates’s entire practice could be viewed as an extension of his roots as a potter, with everything he does as its own metaphorical form of throwing, molding, shaping, glazing, and firing clay, the collective result an ever-evolving form of social sculpture. Gates’s latest project is The Land School, formerly known as the St. Laurence Elementary School, which he and his Rebuild Foundation have reshaped into an arts incubator. It joins several other Rebuild spaces nearby, including the Stony Island Arts Bank, a 17,000-square-foot arts center, archive, and community hub; the Listening and Archive Houses; and the Dorchester Art + Housing Collaborative, a residential community designed for working artists and their families.

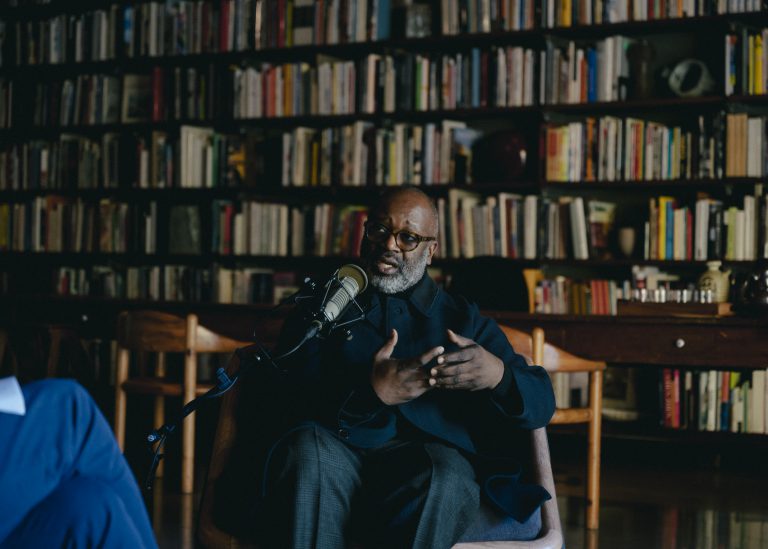

On this episode of Time Sensitive, our latest “site-specific” recording, Gates sits down with Spencer inside his personal library in Chicago to talk about his current exhibition, “Unto Thee,” at the University of Chicago’s Smart Museum of Art (on view through Feb. 22, 2026), which marks his first-ever solo museum show in his home city; his forward-looking vision for The Land School; and the vast, alchemic impacts of music on his life and work.

CHAPTERS

Gates shares his long-term vision for The Land School and reflects on two decades of his Rebuild Foundation.

Following the opening of his “Unto Thee” exhibition at the Smart Museum of Art, Gates considers the University of Chicago’s formative role in his life and work.

Gates recalls his studies in Tokoname, Japan, famous for its legacy of master potters and ancient kilns, which in a roundabout way deepened his appreciation for Mississippi, where his family has deep roots and where he spent meaningful time in his childhood.

Gates contemplates his urban development practice through the lens of pottery. He also talks about his 2024 “Afro-Mingei” Mori Art Museum exhibition, which included a monumental tribute to the late Japanese potter Yoshihiro Koide.

Gates revisits early music memories and his 30-year love affair with records, framing vinyl collections—both his own and those he stewards—as self-portraits.

Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

SPENCER BAILEY: Hi, Theaster. Welcome to Time Sensitive.

THEASTER GATES: Thank you so much. It’s really wonderful to be here.

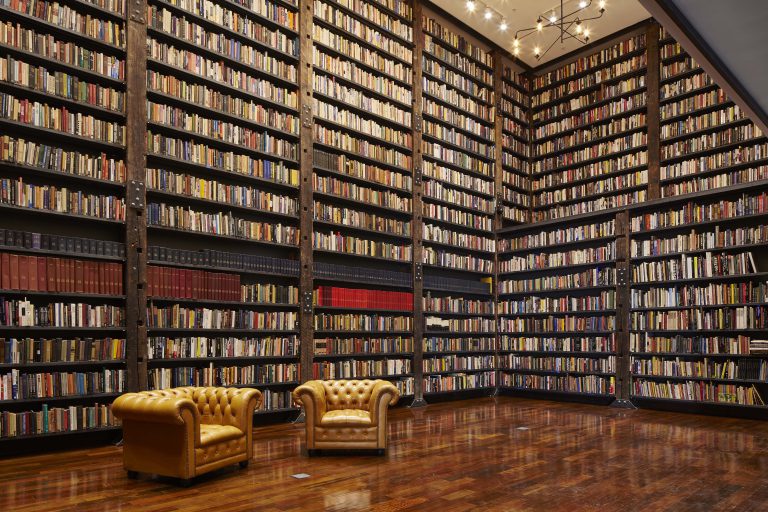

SB: Yeah, in your studio and incredible library, surrounded by books.

TG: Thank you, man. It’s one of my favorite spaces of all our spaces.

SB: Mmm. Well, first I wanted to ground this conversation in The Land School that just opened, and hear a bit about your vision for that, which is just down the street from where we’re sitting.

TG: Yeah.

SB: Could you share a bit about The Land School, the duration of that project, how it came about, and what your aims and dreams are for it?

TG: There are two different kinds of vision for The Land School. The first has to do with what I think is an ongoing demonstration that Black artists, artists, people of color, creatives, can have a say-so in the potential in the future of the place where they live. Even before we get to the mission of the school, there’s the actual construction, purchase, the negotiations necessary with the city administration, with private individuals who buy and sell things… All of that work is an investment in Black space. When people read my biography and it says, “I believe in Black space theory” or “I’m a Black space theorist,” I think what I am is actually a Black space practitioner who uses planning theory to capture and protect the community that I live in, and use that as a demonstration of how others might be able to capture and protect spaces in their communities. So, one part of The Land School is about demonstrating that—after Dorchester Projects, after the Arts Bank—there’s still more work to do.

The second part of The Land School, what happens in the building, that feels like it has to do with the creation of an experimental platform where the cultural activity of the people who live in the neighborhood, the cultural expressions of the coldest musicians, artists, theater, playwrights, poets, fashion designers, creatives in the world, that they would want to come to the South Side of Chicago and participate in the experimentation happening with these cats right around the block. That idea that we could be hyperlocal, and believe in the alumni of the St. Lawrence Elementary School, and that alumni has a presence in our auditorium and our grounds. And also, that if Solange is coming through, that Solange could drop her things and know that her book is going to be protected and that her ideas and advancements could be protected. We want to make a home for the baddest creativity possible, and we want that to happen in the most local ways possible.

SB: I like that you mentioned this way that people frame you as a “Black space theorist.” But actually, I think, what you’re getting at and what you were talking about is that you’re actually as much a practitioner. It’s about Black space theory in action.

TG: Yes. There are lots of people who study urban planning, urbanism, tactical urbanism, landscape architecture. They went to Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, they went to Yale. They do these things. They may have also understood the history of great cities, but they don’t necessarily take that information and do great things for people of color in Black and brown communities. I went to those schools and learned those theories, and I’ve been trying to figure out: Is there a way that you could take that information, that body of knowledge around how cities change, why they change? Who are the characters and principals who change them? Then, with that knowledge, you could then make it work for those who don’t sit at the table all the time.

SB: I feel like we should expand here a little bit to Dorchester Projects and your other work that’s in this neighborhood, all the stuff you’ve built with your Rebuild Foundation, which essentially dates back nearly twenty years now, to 2006, when you moved to this neighborhood. You’ve built out this kind of campus, I guess we could call it: Stony Island Arts Bank, the Black Cinema House, Archive House, The Listening House. How do you think about these past two decades of art-making, placemaking? I guess they’re one and the same. [Laughs]

TG: For me, yeah.

SB: How would you describe your “Dorchester time,” I guess, we could call it?

TG: The last twenty years has felt like I’m riding a two-headed dragon. My studio has been absolutely central to the creation of these projects. In some ways, Dorchester Projects was first an extension of the studio: How can I, as an artist, do more than just make sculpture and paintings and performances? Is it possible that I could use the same brain to have an impact outside the studio? That was the language that I used. Then, the creation of 501(c)(3), a legal entity that was a public charity. How can others participate in the activity that I do, so that the impact could be greater, so that the reach could be further and we could do more faster?

It was the creation of a platform called Rebuild Foundation, and then that coexisting with my studio practice, those two things together, with support from all over the world and so many friends and funders and allies and thinkers and artists, that together created a property portfolio and an artistic and cultural platform that punches well above our weight, I think. People imagine that we’re this huge crew that wants to be something between a community development corporation and a Lincoln Center or something. But in fact, we’re just ten people who are pretty scrappy, using these old buildings to make great things happen, hand to mouth. But it’s the sexiest hand-to-mouth activity I could ever imagine.

SB: [Laughs] I think that there’s something about language here that I wanted to mention—

TG: Sure.

SB: Because I feel like you’ve used language as this really important tool in shaping how people think about space. Could you talk a little bit about that?

TG: Yeah. My training was so varied. When I approached the topic of space, I was sometimes approaching it from a religio-spiritual lens, sometimes from a political-cultural lens, sometimes from a Black radical lens, and then as a kind of urbanist. Thinking about the city from the perspective of policy and histories, and the great characters who have shaped what our cities look like, and the philosophies they’ve used to justify the need for parks, the need for setbacks, the need for a central business district. The need for specialized zoning that would give some things permission to be in a place and other things a non-permission to be in that place.

When you put those language projects together, and you put those theories together, and those histories together, you start to build a new set of spatial poetics or a language that could use urban policy in a Black radical tradition together to make a new language. Or it could take the history of Jane Addams, and the history of Jane Jacobs, and the history of Jesse Jackson, and fuse those three characters into a kind of new cocktail of urban expectation. I expect something different from the city, because I wasn’t only reading Frederick Law Olmsted, I was also reading Huey P. Newton.

SB: I think it’s important to mention here, before really formalizing your trajectory or path as an artist, you worked in bureaucracy—you worked for the city.

TG: Yeah. I worked for the Chicago Transit Authority under one of the most capable people I’ve ever met. A woman named Elizabeth White, Beth White who worked for Valerie Jarrett [chairman of the board of the Chicago transit authority from 1995 to 2003] another uncompromising person when it came to bureaucratic or executive leadership for our city. Because of those two women allowing me, giving me permission to build a transit arts program for the City of Chicago, I learned so much about how the sausage is made, relative to large construction projects. Then the ways in which art could be more instrumental and more present,because I was in the back rooms where the deals were done, and I could tell that art was one of the non-considerations. Just because there was no one there who was skilled enough in urbanism to talk about the arts, as well. Or skilled enough in political truths, whatever they were. Or adjacent enough that they could be selected by a mayor or selected by a commissioner, to hold a post.

I think that I was given this opportunity, at a very specific time, where my passion for the city, my passion for the West Side, and the South Side of Chicago, my passion for the arts, those things all came together to make me who I am.

SB: I think what you’ve shown over the past two decades with this work is almost that real estate development and art-making don’t have to be at odds. Or that art-making can be a form of real estate development, in a way. When did it come into your head that an abandoned building or repurposing an existing structure could be a form of art? Because I feel like that’s not your typical approach.

TG: This is also where language has been really helpful for me. I used to try to call myself a “cultural developer,” but I’ve realized over the years that I’m actually not a developer. I think traditional development has rules that you follow, and if you follow them—and even if you hack those rules—it means that you’ve bought a property for a little amount of money, you’ve aggregated other people’s resources to make it work, and then you have tenants in those properties. Over time, that tenancy generates value and you’re able to pull equity, there’s this whole thing. Where in fact, I am using buildings, they were abandoned, they do require resources. I don’t have tenants. I have a house filled with albums.

SB: [Laughs]

TG: I have a house filled with music.

SB: Yeah, books…

TG: I have a house filled with films. We have houses for visitors. And because of the last part of it, where I don’t have an income that’s generated from it, as a result, developers imagine that, either I’m a bad developer. [Laughter] Like, I’m a developer who refuses to take rent. Or we could help developers understand that there’s something else that people need in our cities, besides a place to live. So, in addition to a place to live, what else do buildings need to do? And in neighborhoods where the commercial district has been toppled and there are no available commercial buildings, then our residential housing stock is what we have to work with in order to create a stabilization force where people want to stay in the neighborhoods where they’re from, even when they have resources where they could live somewhere else. I think we’ve used culture as the stabilizing mechanism, and we’ve used the housing stock as the space where culture might happen.

When I put those things together, I feel more like a person who believes in culture, and buildings are a means to an end, and culture is the end. Money isn’t the end. Being a developer isn’t the end. Significant world transformation, that ain’t the end. The goal is for the young lady who knows how to sing and lives down the street, she would be able to meet other people who are in a choir, and that choir convenes down the street, and that they can all go to The Land School and they could be in a choir together, or there might be other opportunities where she could network, sing her song, learn new songs, learn music theory, et cetera, et cetera.

SB: You’re also creating, it could be called, a “third space.” In a world in which fewer people, to a certain extent, are going to church, fewer people are drinking, not going to bars, we need these third spaces.

TG: Totally. I am thankful for this language of the third space, because it feels like people also don’t really want to be at home, necessarily. Home and the preexisting institutions—in a way, they’re all failing. Where there seems to be room for a social innovation is in helping people imagine that there’s a space besides home, besides the church, besides the bar, where they could be.

I’m also making it up myself. The way that I’m doing it is by asking myself, “Who do I want to be around? What do I want to be doing?” That’s very exciting.

SB: Yeah, and if culture is an end… I love this idea that you’re describing—of culture as an end—because culture actually begins in the ground, in its truest meaning, if we get really nerdy about it—it’s an agrarian term.

TG: Yes.

SB: It was related to this idea of cultivation of the soil. It was Cicero, I think, however many thousand years ago—

TG: Love that.

SB: …who took the word and used it the sense of cultura animi, which means, an animated sense of self, or a cultivation of the soul.

TG: Yes.

SB: If we’re thinking about third spaces, and thinking about the true meaning of culture, it’s actually what it means to be rooted in the ground of where you’re from or where you live.

TG: That’s right. I also think that the extended, the expanded metaphor of the agrarian laborer, the person who sows, that it’s totally reasonable that there’s a part of the work that I won’t see fully realized. My role is to plant and to water, and the buildings, in a way, are the first deposit of seeds. The fact that we already have programs is exciting and things are growing, and we have real gardens, as well. But I think that, for me, the testament to the culture-building that we’re doing today, we may not see the evidence of it fully until twenty or thirty years from now, and I love that, too.

SB: We’re not sitting too far from the University of Chicago.

TG: Right.

SB: I feel like we have to talk about this pivotal place in your life and work. You’ve been a member of the faculty since 2012 and, going back even further, you’ve previously held different roles there, all the way to 2006. Could you just speak to the University of Chicago, its place in your life and work, and how it’s informed and impacted your art practice?

TG: Yeah. I was struggling to find work. At the time, I was a mason’s tender. I was working for my friend Julian Aranda, the brother of a dear friend, Mario Aranda. I’m saying their names intentionally because the Arandas were already a super-sophisticated crew of builders and thinkers. I remember one day calling a dear friend, Jackie Terrassa, who was, at the time, the director of the Smart Museum. I said, “Jackie, I’m mixing mortar and I’m laying stone and I’m building brick walls, and I’d really love a job in the cultural sphere.” And Jackie said, “You know, I think there’s a gig coming up. Let me try to connect you with that team that’s working on it.” Jackie introduced me to a guy named Bill Michel, and I started what ended up being about seventeen interviews to get my gig.

Once I was at the University of Chicago, I met the most amazing people. I met thinkers, writers, creatives, poets— they were all people for whom the life of the mind was very important. Until that time, I really felt rooted in being a ceramic-maker. But then, at the University of Chicago, it made me want to read more. It made me want to think more deeply and express—with language—ideas that maybe I hadn’t ever expressed before.

I feel one of the biggest gifts for me was the athleticism of thinking at the University of Chicago. I felt like I was already twenty years behind undergraduates who had already read all the great books, and they were starting to read philosophy, and they were thinking about [Søren] Kierkegaard and [Georg Wilhelm Friedrich] Hegel and all these folk. And I thought, How am I ever going to catch up? And it was just like a page at a time. I would make my pots and then I would read a little. I would start to think about my pots in relationship to these things that I was reading. And then, there was this guy, Heidegger, and I was so interested in the ways in which Heidegger was thinking about—

SB: Being and time.

TG: Being and time. I feel like the University of Chicago was more than a job. It expanded my worldview, and I’ll forever be grateful for that.

SB: Now, in this full-circle moment, you have this Smart Museum of Art exhibition [“Unto Thee”] that just opened. It’s your first solo museum show here in Chicago, which is also probably a nice, full-circle, homecoming moment. It features all these collections you’ve accrued.

TG: Yeah, it does.

SB: Most of them connected to the University of Chicago. This is stuff including glass lantern slides from the department of art history, the library of Professor Robert Bird, the vitrines from the Oriental Institute.

TG: Yes.

SB: Tell me about this accrual and how it’s all stemming, in a sense, from this engagement with the university.

TG: It’s so interesting, because I think there are a lot of ways to slice what a first exhibition is. I had a great opportunity at the Museum of Contemporary Art a long time ago.

SB: Fifteen, twenty years.

TG: But I think that working with the director Vanja Malloy at the Smart, I felt very much like, if I’m going to do an exhibition on the grounds of the University of Chicago, why don’t I use this as an opportunity to take stock of the material generosity that the university gave me,and demonstrate, in a way—offer back to the university—examples of how I’ve amplified these materials that they’ve given me over time? That if you gave me the glass lantern slides, I wouldn’t just sit on them. If you gave me the slate from Rockefeller Chapel, they didn’t just grow mold and debris and decay. That I was busy about the business of activation. These have been the cornerstones of my artistic project over the last two decades, and I was very proud to offer these things back to the university, hence the title “Unto Thee.”

But then there was something also, for me, quite mystical. The glass slides—not only were they an archive for me, but they were also teaching me a kind of new visual literacy. As a result of that visual literacy, I probably started to understand architecture differently. I understood the modernists differently. And I also saw clearly that there were things missing from the archive. They made me both smarter and more critical of the ways in which the Modernist project or the art-historical project left things out, chose to include some things.

There’s lots of German children’s drawings that seemed important for some subset of artistic theory, but there was no place to talk about the great legacies of the Mexican mural movement, or female artists within Modernism, or Black and brown folk that have been doing things alongside the great periods of art—as long as there have been great periods of art. That absence was very clear to me in the glass slides, so I thought maybe I could have an exhibition that then filled some holes while representing these things at the Smart Museum.

SB: It is a small show in a certain sense. It’s a very compact show. The room that moved me the most in it was the room with the church pews and the slides.

TG: Yes.

SB: You have these three projections going at once, each at its own cadence, and then you have a voiceover going. I caught the poet Fred Moten—

TG: That’s right.

SB: …speaking and it’s just like this meditative haze or something. You fall into a trance and you want to see what’s on all three screens, but you can’t.

TG: Yes. I think, in many ways, the film that I made called “Art Histories,” where I was really trying to create a somewhat immersive environment, because I often feel that’s the way that I learn. I like multiple tracks playing at the same time, multiple images playing on repetition. Visual literacy isn’t just about facts; it’s also about forms. I was quite excited. Say, sixteenth-century Spanish Gothic cathedrals. You look at those things enough, you start to understand a line differently, a curve differently. You look at something Gothic in relationship to something romantic, and you think, Oh, this is so different from the Arts and Crafts Movement, which is, maybe closer to Bauhaus in some ways, that there’s rigidity and fluidity. And by having those images washing over you, you start to develop a lexicon of listening with your eyes. And I love that.

SB: You’re deejaying glass slides.

TG: For sure. [Laughter] It’s also a way of saying that there are multiple truths around the history of a period. What was happening in Vienna, in 1920, was absolutely interesting, but the colonial project in Afghanistan was also very interesting. And the truth of Algeria in 1930 was very interesting. The truth of Nigeria was also very interesting. I feel like there are these moments where you imagine that the world stopped and all that existed was Vienna, and that, in Vienna was this important moment, and no other artistic moments were happening.

SB: Totally. [Laughs]

TG: Or you discover Fiji with [Paul] Gauguin, and it’s like, Oh, no. Fiji pre-existed in the colors that are so romantic that we love Gauguin for, in fact. Those colors were teaching Gauguin how to paint. Those people were teaching Picasso and [Francis] Picabia and Berthold [Woltze].

SB: Of course. And what [Constantin] Brâncuşi was doing in the twenties in Paris, great. But so was what was going on in West Africa.

TG: That’s right. It allows for me to have a dialogue not only about colonialism as we understand it, but about how power and culture have always been intertwined in a complicated dance. , If I could suspend my judgments of the colonial project or of power, but just to say that, power in all its forms is changing how we understand culture. Could we understand Sony or Warner Brothers or music platforms of this moment, Spotify, as a hegemonized power that is then forcing a musician to determine how long a song is?

What if you want a seventeen-minute song or a thirty-five-minute song? What if the truth of an expression is an hour? If Bach had the right to create a two-hour opus, isn’t it possible that D’Angelo has the right to create a forty-minute love ballad? I’m interested in examining power not only from the perspective of “bad white people or good brown people,” but the ways in which the platforms want us to do certain things that we could either say yes to or no to.

SB: I mean, the homogenization is very real.

TG: Oof. I think after six minutes, I’m like, Why is this song still on? You know what I mean? That we almost have no mental capacity to receive long-form anything. Those are the things that help me understand that there’s so much room and potency within art to help us get back to ourselves and back to our humanity: Back to our deep listening, back to our capacity to listen long, see longer, note things more deeply.

SB: Sit on a church pew and look at glass slides go by, while trying to also engage this spoken-word, audio experience. I slowed down in that room in a way that I hadn’t all day.

TG: Yes.

SB: Flew into Chicago, jumped in a cab. But it’s only when I finally get to the museum and I’m in that space… It goes back to third spaces. I think we need third spaces for slowing down.

TG: I agree. Sometimes it just feels like an intuitive gesture within a film or within my artistic practice. But I feel like I’m always wanting to make a space where people just feel safe enough to not have to do very much. And that, in not doing much, they can then get to the business of the soul and the business of the spirit, and all of those anxieties of the day they can slowly wash off. But that takes so much time. You need time. I’m also trying to reclaim some of that time.

SB: This is a very appropriate moment to turn to Japan, because I feel like Japanese culture is all about that. Here I want to turn to Tokoname, in particular,but also Japan more generally. Which, I would say in so many ways, is as much at the heart of your practice, as Chicago is. In 2004, you studied in Tokoname, this coastal city with ancient kilns, a nearly thousand-year-old history of ceramics, learning from these master potters there. Tell me about your entry into Tokoname. What do you remember from that?

TG: I arrived in Tokoname, and I remember my host family, the Tomita family, greeting me, picking me up. The whole family came out and we had to send a letter saying, “What are your hobbies? What are your favorite foods? What are you reading?” I remember saying that my favorite foods were pineapples and scrambled eggs, and watermelon—something like that. Simple things. I said, “I really love fried rice, and I love to salsa dance.” Over the course of my first twelve weeks in Tokoname, every morning I had fried eggs and pineapples. Then on Fridays and the weekends, maybe there would be suika, or watermelon. And I didn’t remember that I had written those things down, but my host family paid such close attention to the things that I loved.

Then, before I was leaving from my first trip, my host mother, Mrs. Tomita, asked if I would be willing to teach her friends how to salsa. I thought, Okay. Yeah. Let’s do it. And one day I arrived back home after being at the workshop all day: There were thirty 60-year-old Japanese women, waiting for me to give a salsa lesson. I had just never been in a place where a community could be mobilized so easily, with so much joy and so much focus toward a specific project, whether it was ensuring that I had my favorite food or ensuring that before I left Japan, before I left Tokoname, that every wish on my list—that in some way it had been acknowledged. I think that that sensitivity to being human, I saw it evident in the way that they raised their children, and the way that my host family dealt with difficult moments. It was really fantastic.

I would also say that Japan was the place where I fell in love with Mississippi again. Because I was in a rural place, Tokoname is somewhat rural, and the pace of it was very much like what I had experienced in Mississippi. But Mississippi had so much stigma attached to it in my brain that I had to go to a place that was like my hometown in order to see my hometown differently. I always say that Japan made me fall in love with Mississippi again.

SB: Share a bit about your “Mississippi time.” Then we’ll get back to Tokoname.

TG: My mom and dad are both from very large families, and they were the two children from their families that left the South during Jim Crow, to come to Chicago, with a pit stop in St. Louis. The rest of their siblings stayed in the South. I’m the ninth of nine children. For years, before I was born, my parents would go every summer, back to the South. When I was born and was of age, which was like 7, I started going with them every year. By the time I was 12 or 13, I could actually ride Greyhound by myself. Sometimes my mom would send me to Japan—I mean, to Mississippi.

[Laughter]

SB: Good flip.

TG: Yeah. She would send me to Mississippi on my own, and I would work in the fields with my cousins. Which meant we were planting cotton, soybeans, corn, and then, minor vegetables.

SB: This is on your uncle’s farm?

TG: On my Uncle Hubbard’s farm. Really, it was my mom’s way of making sure that I was safe from the city during the summer, when she was working. But it also taught me a work ethic that was unbelievable. It was a different time, where you wake up at 4:35 a.m. You want to beat the heat. In other places, you would call it a siesta, but it was like, if the blazing heat from 11:30 a.m. till 2:00 p.m., you’d have an extended lunch and then you would go back to the fields after the sun was a little less hot. But in that period, I learned so much about the rituals of labor, the value of work. And not in a grossly Calvinistic way or in a way that was esteeming work above all things—it was like, work sustains us. When we plant things, we benefit from the growth of those things.

SB: The fruits of your labor.

TG: We will have excess corn, and we’ll be able to give that to our neighbors and sell it to our far neighbors. I loved how productive the Allen family was, my mom’s family, and I think that that ethic of waking up early in the morning, going around, looking at the fields, checking on the buildings, making sure everything’s good, the cows are good, the hogs are good— I’ve carried that ethos, that way of working, into my artistic life.

SB: So you see a direct link, say, from the farm work in Mississippi to the pots you were making in Tokoname?

TG: I’m pretty convinced that what helped me receive an invitation back to Tokoname was the work ethic I developed as a young person in Mississippi. I was very young—24, 25. What my mentors saw was, “Oh, this guy doesn’t make pots really well, but he’s willing to work.” I think maybe I still don’t make pots the best; I don’t make art the best, but I’m willing to work. I’ll work very hard. I’ll outwork most people.

SB: I think some people would disagree with that statement in terms of you not making good art. [Laughter] Taking it back to Tokoname, a few years ago, at the Aichi Triennale, you created this listening room [“The Listening House”] there. Could you talk a little bit about that as an experience, but also just, more generally, the fact that you keep going back?

TG: Yeah. It was really beautiful. I have a dear friend in Tokyo, his name is Mr. Obayashi. And Obayashi is the chairman of the Aichi Triennale and a very amazing art collector, a classy guy. It was at Mr. Obayashi’s invitation that the curator and Obayash-sani invited me to come back to Tokoname, my hometown, and be a core ally in this Triennale in 2022. I kept thinking, I can’t bring pots to Tokoname. That would be weird. What could I give Tokoname? I decided that I would create a listening space. I would take this former pipe manufacturing, ceramic pipe manufacturing company, and I would turn the principal house into a space for soul music. I would bring the things that I love from Chicago, I would bring them to my other hometown, Tokoname. I thought that the potters in the city and friends would really enjoy this much more than they’d enjoy looking at more vessels.

So that’s what I did. I brought a lot of Aretha Franklin. I brought a lot of Donny Hathaway. And I brought the collection of a Chicago potter named Marva [Lee Pitchford-]Jolly. She was very important to me, and Marva always wanted to go to Japan. When she passed and she bequeathed me her albums, I thought, Oh, I should bring Marva with me. It was a magical time. I was so surprised that people knew the lyrics of Sly and the Family Stone, and they knew Donny Hathaway lyrics, and they knew who Marvin Gaye was. Soul was alive in Tokoname, and had been for a very, very long time.

After that time, I became very endeared to the house in Tokoname. It was a compound—it was the house, and then it was a newer house and a workshop space, and a space for manufacturing and a kiln space. I decided, as a tribute to my time there, that I would acquire the compound, and then make that my principal working space in Japan.

SB: Wow. That’s incredible.

TG: It’s really special. It feels like in some ways, Tokoname was slowly encouraging me to come back. The work that I have been doing in Chicago, I feel very much like, some of that work is starting to take root in Tokoname.

SB: I think what’s interesting too is, first and foremost, you’re a potter.

TG: I’m a potter.

SB: What’s amazing is actually, it’s all this other work that’s created a halo back to the pottery.

TG: In so many ways, I feel fortunate that I was able to start by touching things, by using this material. And by using the material, I became interested in the history of the material and who else was using the material. While I probably wouldn’t have picked up a book just to pick up the book in undergrad about ceramics, because I was touching the material first, it made me so curious about all these histories. Then, I became deeply invested in the history of clay, which meant that I was also learning about other things—the relationship between China, Japan, Korea, the way in which Buddhism spread; the relationship between India and China. Early philosophies that governed the sensibility of people, the sensibility of imperial leadership or executive leadership over a country, why wars broke out. How cousins became countries, this kind of thing. And I feel very much like I would not know world history if it wasn’t first for an encounter using my body with this material.

SB: It’s also worth saying, you studied urban planning and design in school, but you did have this pottery class. I think about this as what you were talking about earlier with Black-space theory, but then putting it into action. Do you think pottery was, in a way, a method for you to see that thing in action in your hands and realize how to scale it up? I guess a different way of framing the question would be:, Do you view the buildings here, the work you’re doing at an urban scale, as a form of pottery?

TG: Initially, when I started making things, my goal was quite practical. Like, “I’m going home for Christmas break, I need twenty gifts because I have a lot of nieces and nephews and sisters.” That worked for the first few years. Over time, clay started to take on a metaphoric symbolic program. That I would make a thing and I would ask, “Why am I making the same thing over and over?” I realized that, Oh, this is about, not necessarily having a thousand things, but practicing so that you can make one great thing. That you need to have made a thousand things in order to get to the thing that you really love. So, the thing that I really love, it’s inside me, but it’s a thousand throws away, let’s say.

Then it became even more nuanced, where I started to imagine perhaps the preoccupation I have isn’t necessarily with a cup or a pot or a bowl, but the idea that there’s a container needed, and I have the capacity to create the necessary vessel for the things that are needed in culture. And that vessel could be a small vessel, or it could be a very, very large vessel, or it could be a series of very large vessels. And I think that the city is a series of very large vessels.

SB: Linking Japan and Chicago here, because I feel like I gotta get a question in bringing the two together. I think it’s just obvious we should talk about “Afro-Mingei”, this sort of concept, which also became an exhibition at the Mori Art Museum that I was very fortunate to get to see—

TG: Thank you for seeing it.

SB: —from last year. I should mention to the listeners that Mingei refers to a Japanese movement that started in the 1920s and really celebrated the beauty of the everyday—

TG: That’s right.

SB: —or even the seemingly mundane, these craft objects like the teacups we have here next to us. This exhibition—and really installation, or series of installations—was so astounding at the top of this tower, in the middle of Tokyo. I wanted to bring up one in particular, which was Yoshihiro Koide’s pots. That he was a potter who had passed away in 2022. You created this, I guess I could call it a monument. Certainly a monumental installation. Could you talk about Afro-Mingei and that particular installation?

TG: Yeah. Part of the reason that I love the Mingei movement, [is that] it’s all the things that you said: the celebration of the everyday and the ordinary, and beautiful things made for everyday people. But it was also doing that in the wake of Westernization and an external force impeding on Japan, maybe trying to change its language values, its fashion values. Instead of wearing a kimono, maybe you can wear a Western dress, and you could have a three-piece suit. Instead of factory life as we had understood it in Japan, maybe it’s time for you to adopt Western versions of the eight-hour workday. There was a lot of cultural resistance to Western influence. That part was also very interesting to me.

Afro-Mingei, then, was my thinking about the Black is Beautiful and Black Arts movement, where it was like, “Hey, we also can resist some of these externalisms that say our hair has to be like this. We have to wear this.” It was this movement where Black folk were like, “I want to wear a dashiki. I’m going to wear an Afro. I’m going to wear my hair in plaits. I’m going to celebrate the history of our legacy.” I felt like Mingei and the Black is Beautiful Movement had this thing in common. Afro-Mingei, then, was like, could I take this history of Black liberation theology of [W.E.B] Du Bois, of Marcus Garvey, of my interest in the important poets—of Nikki Giovanni and Audre Lorde? Can I take all of these ideological and literature traditions, and combine that with Zen? With a notion of Buddhism? With the idea of more singular practices? Going deep, instead of going wide, which has been my multidisciplinary way of working? Is it possible that Mingei and varying Japanese ideologies could give me a stabilizing—a new, stronger core? And with that core, I would have alongside it, all these philosophies that have made me.

I feel like, in some way, it wasn’t that I wanted to bastardize Blackness or bastardize what I knew of Japan; it was that those influences were, in some way, informing my sensibility around architecture, my sensibility around design, my sensibility toward composition. So that the way that I wanted to paint or make started to really change, and I wanted to acknowledge that. Even if people couldn’t put a finger on it—or they might think, oh, this looks very Bauhaus or very Swiss, that in fact, it was this amalgam of circumstances and ideas that had come together. It was definitely influencing my artistic practice. It was a way of giving a shout-out to the power of Japanese culture to help me be a better maker.

SB: In some ways, you’re the hyphen in Afro-Mingei.

TG: Absolutely. I’m right there in the middle.

SB: Tell me about Yoshihiro Koide and this collection of pots that I was mentioning earlier.

TG: So, I had gone back to Tokoname and I needed a wood kiln to fire in. My dear friend Koichi Ohara said, “Oh, there’s a guy, his father had recently passed. Why don’t you talk to him? Because that kiln is not in use.” I went to visit the son, and the son said, “Of course you can use my kiln, but I also have all of my father’s vessels, his work, and I’m not exactly sure what to do with it.” And Mune-san, who’s amazing— He teaches Japanese, the language, in Korea, and he is a scholar and a teacher. We just hit it off, we became very cool. When he had this problem of what to do with his dad’s corpus, with this collection of works, which was probably close to fifty- or sixty-thousand objects, it seemed like my kind of problem.

[Laughter]

Because I had this exhibition coming up at Mori, I thought, What better way to celebrate Tokoname, than to have the life of one person, and all of the work that he had made over his entire life that was available, and to show this body of work in one go? Not from the position of a specimen or “this is the best of his work,” but to show his entire life. The Koide monument: It was my attempt at honoring Mr. Koide, but also a way of celebrating Tokoname. It’s one of the individual artworks that I’m most proud of in my life.

SB: I would call it heroic. I mean, this thing is—

TG: Thank you so much.

SB: I was reading this incredible story that resulted from your Mori Art Museum exhibition. You were approached by the widow of the late journalist Ei Nagata, and given another incredible collection.

TG: Oh my gosh.

SB: Can you share this story for the listeners?

TG: Again, if we think of Afro-Mingei as a kind of speculative project, it’s a proposal about, what if Black life and Japanese life were to merge? I have this exhibition, it’s a huge exhibition. It’s thirty thousand square feet. It’s a huge, huge space. And I think that the idea of the Black experience and the Japanese experience, it affected lots of Japanese people and Blacks in Japan, in ways that I didn’t know. So I was given audience with this amazing woman, Haruhi Ishitani, and Haruhi said, “I was present at the assassination of Malcolm X. I was a young student, and I was there with my partner. Over time, we went on to write about Malcolm X, and we also translated many of his speeches.” Ei Nagata, her partner, who was a young budding journalist, went back really advocating for talking about the atrocities in the United States and the assassination of this great leader. They both had socialist leanings and for many years committed themselves to the translation of Malcolm X’s speeches.

When I met Haruhi, she was then 87 years old, and she said, “I have this archive of things that include broadsides and socialist manifestos, and all of my photographs and our photographs, and I don’t have a home for them. I’m showing a small exhibition at a revolutionary bookstore. Would you come to the bookstore and see the things?” I did; I was overwhelmed. And we worked out a stewardship plan for the collection. And now I’m the steward of the Ei Nagata, Haruhi Ishitani, Malcolm X Collection.

SB: I mean, it doesn’t really get more incredible than that.

[Laughter]

TG: It’s almost like the archive begets archives, when people can tell that you’re willing to go the extra mile to care for other people’s things, which is essentially what a museum is, right?

SB: But you’re not just caring for them. You’re bringing new life to them. You’re rethinking what an archive is—which I think is, part of the work. It’s not just about keeping it safe and putting it on a shelf.

TG: That’s right. Even my definition of care assumes that the thing would be active. That care isn’t inventory and “put it away.” Care is amplification and dissemination.

SB: All right, we really haven’t talked enough about music yet, and I feel like so much of your practice is about music. It’s this recurring element that’s always present, even if not literally. Taking a long view here, tell me about music in your life. What are your earliest music related memories or touchpoints? How do you think about those in the grander context of music now in your art practice?

TG: Yeah. There was a woman at New Cedar Grove Missionary Baptist Church, the church that I grew up going to in Chicago, on the West Side. Her name was Sister Dyson, And she was the wife of Reverend Dyson. She was an organist. She had the Black gospel songbook in her heart. She could just recall any song and play it and teach it. She was also the choir director for the senior choir, the more adult choir, and I was in the junior choir. For some reason, this question is making me think about the power of Sister Dyson’s voice. She was a chainsmoker, and she had a very husky, low alto voice, and she was phenomenal. But between Sister Dyson, Deacon Bond, Reverend Cooper, Reverend Dyson, Sister Amoson, Sister Patrick, my boy Dwayne Patrick—there was this arsenal of, Dr. Watts, spiritual dirges, what we would imagine as blues form, but they were just old spirituals combined with the most contemporary gospel music of the time, which would include, Mississippi Mass Choir, the Florida Mass Choir, the Thompson Community Singers, John P. Key commissioned the Winans, Yolanda Adams. My earliest world was the full moniker, the full monolith of Black gospel music.

It was always around. Whether it was Mahalia Jackson and Shirley Caesar at home on a Sunday morning before we went to church, The Mighty Clouds of Joy… My gospel well goes deep. Sometimes when I’m at the studio by myself, songs would just come and I was like, “Oh.” The other day I was in the studio and I was thinking about Reverend Cooper, who was the pastor after Reverend Dyson, and he would sing this song “By the grace of the Lord, I’ve come a long way. By the grace of the Lord, I’ve come a long way,” and he had this whine. Man, he could do things, you know what I mean?

But it was hearing these vocals and these vocalics, these ways of using the throat and the stomach and the chest—using your mouth to make sounds, I became as interested in the sound as I was in the word. And I think, over the years, I was interested in the ways in which, gospel could become abstracted. That it didn’t have to just be a trajectory of gospel to early R&B or to blues, to jazz, to R&B, it could also be like, these sounds mutated, could do this other thing. I became very interested in, what if we kept the power embedded in the vehicle of gospel, but we were able to ride that vehicle into other directions? Non-word–based directions, other spiritual futures, other intense political ideas. Could I put other lyrics on top of these things that were more philosophical, ideological, and not necessarily sexual, commercial in some way? There are other things to sing about using this vehicle. I started doing that.

Over the last forty years, I’ve just had a preoccupation with, what if we went back to the root, my root, which is a Mississippi, baptized-in-a-river, Dr. Watts? What if we went back to Dr. Watts, back to the dirge, back to the Mende people, and we were able to then create new trajectories of Black music? I feel like I’ve been playing with that, and I think as I get older, I’ll play with that more and more and more.

SB: Well, yeah. The Black Monks, I feel like that’s a huge component of this, right?

TG: Yeah.

SB: How did that group form, and how have you seen it evolve?

TG: I started The Black Monks as a demonstration of the power of music from the Delta, or music from Mississippi and from along the Mississippi, how that music just migrated all over the world, and it has affected all music that we know. We would not have rock and roll if it wasn’t for—

SB: Muscle Shoals [Sound Studio in Alabama].

TG: Muscle Shoals. I always think about B.B. King and Muddy Waters, but it’s because they have the same Mississippi Chicago connection for me. But I also think, Howlin’ Wolf and all these figures who were important, but also, was it possible that, because of the tremendous creativity and genius of Black people, that we would invent music and then move on, and others would pick up the music and stay there? So that an expansive Dutch jazz, experimental jazz sound, that thing is growing in the Netherlands and in these places, because they’re like, “Oh, this is enough for a whole world of music, and we could just stay here.” And it’s like, “Oh, the blues form, we quickly got bored with that, but white folk ain’t bored with the blues form.”

I think that idea that creative people—Black people, but also creative people—have the capacity to continue to iterate new forms. When you have the capacity to iterate new forms, sometimes you’re like, “Oh, like Miles, I’ve done that. I’m not going to play bop all my life. I can’t play bop all my life.” I’m also interested in the ways in which we could go back to some of those things that we iterated and dropped, and ask, “Is there still more meat on those bones?”

SB: Tell me about these collections, too, these record collections that you’ve accrued. Which are Jesse Owens, you’ve got the Dr. Wax record store, D.J. Frankie Knuckles, Dinh Nguyen, which is a collection that’s in your Smart Museum exhibition.

TG: It’s true. The world is not short of things. My preoccupation with records now, it’s been a love affair of thirty years. As soon as I recognized in my early twenties that I was really an analog guy. I like transistors and I like pushing buttons, and I like turning knobs. Clay was probably also a pretty big part of that. The analog world is just so interesting. I developed a nose for important moments within the analog. I think collecting records was not only about listening to music; it was about preserving a way of being in the world. Sitting around in the basement and listening to a good album, and everybody’s listening to the album.

It’s like the radio station: You can’t control what comes on, but if you want to listen to that Smokey Robinson over and over again, you can. If you want to listen to that Earth, Wind, & Fire, you can just put it on your favorite cut until it scratches. I think that, for me, Each of these collections—Lerone Bennett Jr., the senior editor of Johnson Publishing, Jesse Owens, Marva Jolly—are so particular to the personality of someone.

SB: It’s a portrait.

TG: It’s a portrait. It was like, “Oh, I don’t want to combine them all.” I keep talking about them not as my albums, but as these individual collections. Because, they’re such a clear snapshot of a person in their life of being, in their life of particularity and specificity, and I love that.

SB: I also think there’s something about listening to vinyl. Back to the analog, deep listening—you can’t do that on Spotify.

TG: It’s true.

SB: You just can’t. The audio quality is not the same, the texture of the sound’s not the same. I feel like you’ve also really taken advantage of this, too, with how you present the sound. Devon Turnbull Speakers—that’s a different level of listening than just playing something from your iPhone.

TG: There’s the analog part, but then there’s the connoisseur part. Where it’s like, if you’re going to make time to do something, the situation, the environment of it should be the most ideal you could make it. That’s about taste and about having a sense of the quality of a sound. Once you have a good speaker and you have a good amplifier, you have a good wire, you need a good version of the album. That could get pretty wild quickly. But what I’ve tried to do is demonstrate that, in life, we should constantly try to cultivate a life of excellence in the things that we do. We should try to get better and better with the things that we have.

If I had two books, all I had was two books, I would want to read them until I had them memorized. If I have more books than that, I’d want to be able to create a library that other people could really benefit from. I feel like, right now, I just started reading a book about the history of this library in Paris, and it has me fascinated. Because it was like, these questions of, who has the right to come to a library? Is the library or is knowledge only for a certain class? How can you make a space of knowledge and learning a place for all?

Then you get into these ideas of early [Melvil] Dewey and the foundation of the University of Chicago. Even in these racist caricature moments, there was this idea, there’s a philosophy that I could hold on to, which is: Everyone deserves the right to learn. Learning has never been both more easy or more complicated, because of the number of distractions that we have from the possibility of deep learning. I feel like, for these years, I’ve been trying to create an environment where I could commit my life to a life of just cultivating, learning more about myself, learning more about the world, and being able to share that with as many people as I can.

SB: And presenting a library, an archive, as art.

TG: Yeah.

SB: I think the way that you’ve shown books in a different frame, let’s say, than a lot of people walk into a library, and they’re like, “Oh, this is how I experience books.” But You’ve created these library installations, we could call them, where all of a sudden, they’re elevated and presented in the same way as a ceramic sculpture or a painting on the wall.

TG: Yeah. Let’s say in the case of Robert Bird, you’re looking at a portrait, in the case of Koide-san, you’re looking at a portrait. In this way, the library is both a body of knowledge and a reflection of one’s existence. I feel like, Oh, I’m making portraits. I’m making paintings.The library for me is a painting, and a sculpture, and a portrait, and a body of knowledge. The fact that one thing could do so many things—that is really exciting to me.

SB: What’s it like for you to sit inside this painting that we’re in right now?

TG: We’re in my library on the South Side of Chicago. I have these books because there’s an amazing… Well, there’s many reasons but, one is that there’s an amazing used bookstore here called Powell’s Books. And I’ve been spending more time with the owners of Powell’s. It could be that maybe a part of me wanted to get a Ph.D., and I wanted to maybe commit myself to just a life of the mind, but there were too many things that I wanted to make and do and build. I think that we’re surrounded by books today because there’s something aspirational in their presence. It means that I’ll never get through reading them all—that’s not the point. The point is that, if there’s a place where I should posit my investments, it’s in the pursuit of knowledge. I feel like this room is part of my pursuit.

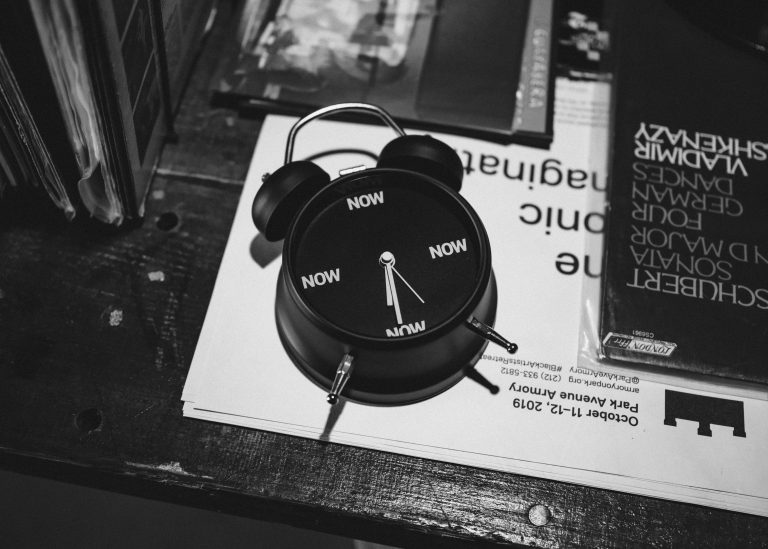

SB: Well, I have one final question for you, because I feel like we skimmed the surface on time. We didn’t really talk about the subject of time. Maybe because time flew by, but I wanted to ask, how do you think about time in your life and in your work? I think in asking about time, also, in the context of your work, I want to use words such as distance, presence, and grief, all of which I think are central to how you explore time. What comes to mind for you when you think about time and those three words?

TG: As soon as you said it, it reminded me of an interview that I did with Martin Puryear, and this always comes back to my heart. We were talking and we had gotten through our interview at the Art Institute. At the end [Editor’s note: Listen to this exchange at 54:46], he said, “There’s one thing that I wish for you. I wish for you time. I wish for you to make time, to pause, to journal, to reflect, because you’ve been so busy.” And Martin is very stoic— He’s a person with pause. He retreats out of the city and he lives out of the city, and he lives outside of time. He lives outside of New York time. There’s one part of me that thinks that time is always this project that, to be masterful of it, requires a tremendous amount of discipline and denial. It’s a kind of discipline and denial that I’m still working toward.

Then there’s the kind of eternal time. I always feel like I’m talking to my mom and dad, even though they’re not here. There are moments when I need to talk to them, but they’re not on this earth. I feel like in some way there’s a continuum, because of the things that they’ve said to me in the past. Those things are maturing in me, even though they’re not here to say them today. In that sense, time feels … maybe there needs to be another word that’s more metaphysical that I don’t know. But time feels like an ongoing and eternal conversation. And I feel like I’m having that conversation with [László] Moholy-Nagy, with Josef Albers, with the living Carrie Mae Weems. I’m having it with my Uncle Calvin who passed. I feel like I’m in conversation with all these characters and they’re helping me be the best 17-year-old I can. Because, when I think about myself, I don’t think of myself as my age today; I still feel like the 17-year-old who’s at the beginning of his interest in learning, and I still feel like I’m at the very beginning of my interest in learning.

Then there’s this idea that, with the project that I’ve done, with The Land School and the Bank and Rebuild, there are moments where I feel like I’ve done what I need to do. That in a way, one of my favorite gospel songs, “Time Is Winding Up,” and it’s like, time is something that allows people to have grace. I can be graceful in acknowledging and accepting that I’m no longer 17, that I’m actually 52. As a result, there are things that I need to put in place, so that my voice can be an echo into the future for others. It’s not me screaming and wailing asking the future not to take me.

I do think about the lifespan of things and how to extend the life of things, but I think that I’ve done so many of the things that I want to do in the world that really matter. Now I feel like, oh, there are others who could probably do this with much more vigor. I’m thinking a lot about how to pass the baton, how to share the load, how to train and inspire, so that I could enjoy this more disciplined quiet time myself.

SB: The Martin Puryear time.

TG: Yeah.

SB: Theaster, thank you. This was really a pleasure.

TG: Thank you so much.

This interview was recorded inside Theaster Gates’s personal library in Chicago on Thursday, October 30, 2025. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. The episode was produced by Ramon Broza, Olivia Aylmer, Mimi Hannon, and Johnny Simon. Illustration by Paola Wiciak based on a photograph by Rankin.