Episode 146

Hans Ulrich Obrist on Art as a Portal to Liberate Time

The Swiss-born, London-based curator, art historian, and Serpentine Galleries artistic director Hans Ulrich Obrist moves through his life and work with a deep internal sense of urgency. Among the most prolific and everywhere-all-at-once people in the world of art—whose peripatetic path has taken him from a sheltered upbringing in a small Swiss village to his current post in London at the Serpentine—Obrist has been curating shows for more than three decades. During this time, he has recorded conversations with thousands of artists, architects, and others shaping culture and society.

Obrist’s mind, as with his projects, traverses many boundaries and realms, and tumbles down various rabbitholes, from art and architecture, to fashion and design, to philosophy and technology and music, to writing and poetry. He is a polymath, in the truest sense of the term, and an auto-didact whose trajectory as a curator has been shaped by his incredible skill at making myriad across-time connections and present-day key introductions—and, importantly, actualizing ideas and realizing projects. He’s also the author of dozens of books, most recently Life in Progress (Crown), released in the U.K. this fall, with the U.S. edition coming out next spring.

On this episode of Time Sensitive, Obrist reflects on 25 years of the Serpentine Pavilion, which has become a defining annual moment in culture globally and a springboard for many of today’s leading voices in architecture, including Lina Ghotmeh (the guest on Ep. 129 of Time Sensitive), and his firm belief that we all need to embrace more promenadology—the science of a stroll—in our lives.

CHAPTERS

Obrist talks about the origins of his Brutally Early Club and his meaningful time spent with the late architect Frank Gehry (1929–2025).

Obrist looks back on his decades of conversations with artists, architects, and others, including Etel Adnan and Louise Bourgeois.

Obrist recalls his childhood spent in the small Swiss town of Weinfelden and his formative engagements with art, literature, and language that led him on his current peripatetic path as a curator.

Obrist discusses his nearly 20 years at London’s Serpentine Galleries, why he finds its “blurring between inside and outside” compelling, and the importance of embracing serendipity.

Obrist considers the vast range of unrealized projects in his mind—many of which he hopes will be realized, at least in some form, someday.

Follow us on Instagram (@slowdown.media) and subscribe to our weekly newsletter to receive behind-the-scenes updates and carefully curated musings.

TRANSCRIPT

SPENCER BAILEY: Hello, Hans! Welcome to Time Sensitive.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST: Hi, how are you? Great to see you. Thank you.

SB: Yes, and at long last. I feel this conversation has been a long time coming. When we ran into each other about a year ago at Art Basel Miami Beach, I’d told you about this podcast, and you instantly had about a dozen references rolling off your tongue about time. [Laughs]

So, I should say here that we’re having this conversation at 8 a.m. on a Saturday. It’s fairly early in the morning, but technically, not early enough for your Brutally Early Club.

HUO: Yeah, that’s true, the Brutally Early Club was, actually, always at 6:30 a.m. It happened because I moved from Paris to London in 2006, and I realized that it was complicated to plan meetings with friends. I always had to plan them a long time in advance. Because also, the distances in London are just so much bigger. It can take, easily, an hour to get from one part of town to the other part of town. Somehow, it’s difficult to improvise gatherings, but I think the best gatherings are still the ones we can do impromptu.

We were with Shumon Basar and Markus Miessen, thinking, how could one do this in London where we couldn’t just say, “Let’s meet at midnight at the Café de Flore”? That sort of thing didn’t work. We had to plan it. Then, we thought, if we do it at 6:30 a.m., nobody can say that they have a prior schedule. [Laughter] It kind of worked; people did really all show up. It was also a club without a fixed home, so to say, without a fixed place, because we just had to find cafés and coffee shops which are open at 6:30 a.m. That actually was, anyway, quite interesting—to see what was open. Bar Italia, in Soho, which is such an important place for art in London—so many artist meetings happened there. Bar Italia is, of course, open twenty-four hours, so Bar Italia was always a venue.

Then, at a certain moment, quite a lot of artists complained that it’s actually not a good idea to do this at 6:30, because if we would do it slightly earlier, then it would work for early risers, but also for people who go to bed late. It would be more of an overlapping, so people could come directly from a club or from a party, wherever they are, and then, those who go to bed earlier, like me, could then get up at 3. So then we did the Hyper Early Club at 3:30.

SB: [Laughs]

HUO: And that, again, led to a very interesting choice of place, of: What is open at 3:30 a.m. in London? One of our favorite places became the coffee shop next to the railway station in St. Pancras, which is basically an extremely busy coffee shop all night long for people who missed the last train.

SB: Well, I’m thankful that this isn’t the 3 a.m. version of that. [Laughs] But speaking of this particular moment in time—it’s Saturday, December 6th, 2025—I wanted to bring up the architect Frank Gehry, who passed away yesterday, at age 96. You’ve done several great, long conversations with him, featured in your book Lives of the Artists, Lives of the Architects; you’ve collaborated with him on the 2008 Serpentine Pavilion. Could you just reflect a bit here on your time with Frank Gehry and its impact on you and your thinking?

HUO: Yeah, it’s important to remember Frank Gehry today. In a way, we’ve probably recorded about fifteen conversations with him over the years, and very often, we saw him with Bettina Korek in Los Angeles. She’s also how we met.

SB: Yes!

HUO: But then, also, of course, because I’m senior artistic advisor to Luma Arles. I’ve worked very closely with Maja Hoffmann from the very beginning on this project of Luma Arles, and, of course, Maja commissioned Frank very early on, at the very beginning of the project.

I always remember she organized a meeting, actually, in Zürich, of the core group, together with her, this new institution, with Tom Eccles and Beatrix Ruf. She also had two artists in this group, Philippe Parreno and Liam Gillick. So we gathered in Zürich, all together, and she told us that she had actually commissioned Frank Gehry to do the building. It really began with that. Luma Arles began with this project Maja did with him. We obviously also saw him a lot there, and did many conversations.

I remember we did an exhibition [“Solaris Chronicles”] with him, actually, when the building was under construction, because often, it’s interesting, when a new institution happens, what happens in the prefiguration or what happens in the process.

SB: Mm-hmm.

HUO: We had a conversation with Frank, and he said, “Why don’t the models move?” We basically had Tino Sehgal—several artists were involved in this show; again, I think, Liam Gillick and Philippe Parreno were involved. We basically started to move the maquettes. Tino developed the choreography for Frank Gehry’s maquettes, and they danced through the space.

And Frank said, “We need a soundtrack for this show.” Obviously, he had this deep connection to music. Music was so important for him.

SB: Not just Walt Disney Concert Hall; he loved music.

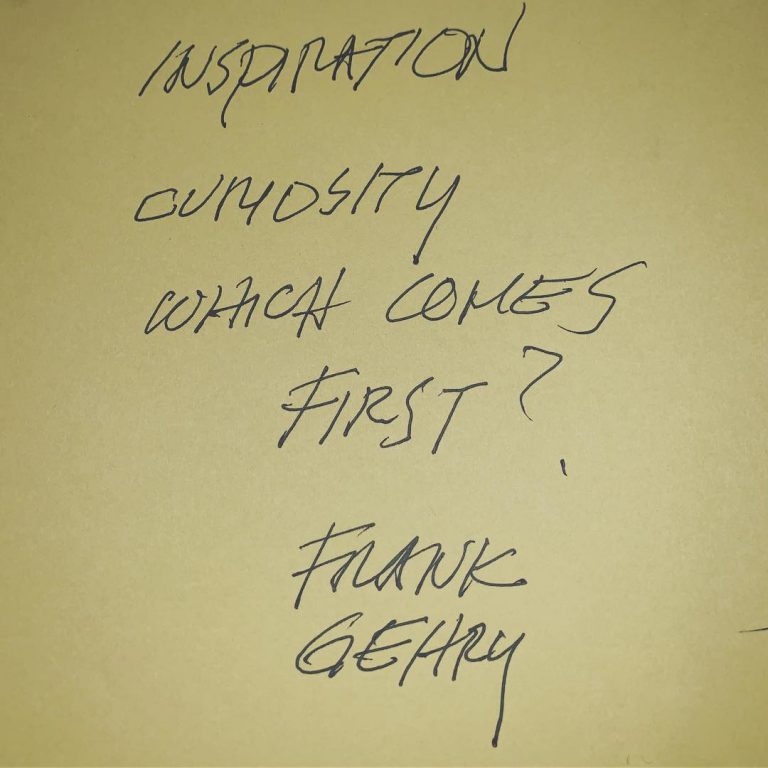

HUO: He absolutely loved music. He once said—he wrote this for my Instagram, because I’ve got this Instagram with the handwritten notes—he wrote, “If architecture is frozen music, is music liquid architecture?” Which is a great quote.

I asked him, “Who could be the composer?” He immediately said Pierre Boulez. So I rang up Pierre Boulez, and Pierre Boulez was in his nineties. He was more or less the same age Frank Gehry was at now, and actually, he was not in Paris anymore, he was in [the German town] Baden-Baden, in this big, empty house near the park in Baden-Baden. So I traveled to Baden-Baden and went to see Pierre Boulez. And I said to Mr. Boulez, “Frank Gehry suggested that we have this soundtrack.” And he said, “Anything Frank wants…”

SB: [Laughs]

HUO: So we had this conversation. He came up with a very beautiful soundtrack for the show. We have to imagine: the models dance through the space; there is a soundtrack of Pierre Boulez.

Then there was another prefiguration project [“To the Moon via the Beach”], where, in the arena of Arles, with artists… The beach was basically [made] with sand. A moon architecture and a beach architecture transitioned, or went from one to the other. It was really interesting that that sand later on then became part of the building. There’s so many layers to that story.

SB: Yeah, fifteen conversations, as you said. That’s one of the things I love about your work. It’s these deep, ongoing dialogues, often that start in conversation and then manifest these physical or ephemeral things out in the world.

HUO: I found a few Post-Its, actually, last night—I went through the archive—that Frank wrote for me. One is, “Inspiration / Curiosity / Which comes first?” Another one is, “This is my handwriting. / This was my handwriting.”

SB: [Laughs]

HUO: There is also the one about… It’s a longer one about the Barcelona Pavilion. He wrote, “Minimalism and simplicity get conflated. The Barcelona Pavilion is minimal and probably considered simple, but the convention…” What does it say here? Can you read it?

SB: Hans has passed me his phone. “Minimalism and simplicity get confused. The Barcelona Pavilion is minimal and probably considered simple, but the connection…” Let’s see. I actually don’t know what he says here. “M-O-O to wall if you…” This is classic Frank, because I can’t make out his handwriting. [Laughs[

HUO: I can’t read it, either. It’s so funny. “But the connection…” No, now, I think I’m sure—now I get it. “But the connection of roof to wall,” and then it gets complicated again.

SB: [Laughs] This makes me think about all this rarefied time you’ve been able to spend with these many artists and architects and others who are no longer with us, from Philip Johnson to Louise Bourgeois to Etel Adnan. And I’m sure the list is hundreds, if not thousands. But how do you think about this precious time that you get to spend? And now that so many of them are no longer with us, what does it mean to you to have this archive of conversation, these documents of your time with them?

HUO: Yeah, Etel Adnan, the great poet and artist, she always told me that we have to learn to listen again and pay attention, and listen and listen again. I think that’s, in a way, what the project has been from the beginning. It’s about listening. But it’s also about thinking how these conversations could produce reality. Because very often, I basically ask about the unrealized project, and, of course, there is a very broad range of why projects are unrealized. I think we all have unrealized projects. Some are too time-intense. I think that’s probably one of the main reasons why projects are unrealized: We just don’t have enough time in our life.

Friederike Mayröcker, the seminal Austrian poet and writer—I always thought she should have won the Nobel Prize for literature. She’s, for me, one of the greatest poets of the twentieth, twenty-first century. Friederike Mayröcker, when she was in her nineties, told me once, “I have another century of literature to write. I have a time problem.”

SB: [Laughs]

HUO: So, obviously, some of these—and she’s written more than a hundred books, but she really had many more books she had in her mind. So, time… Sometimes there isn’t enough time. But it can also be that a project is too big or too small to be realized. It can be that it’s too expensive to be realized. It can also be that it’s fully or partially unrealizable.

Siah Armajani wanted to make a sculpture from the Earth to the Moon—the late American-Iranian artist who lived in Minneapolis—and that’s an unrealized project because it’s probably unrealizable, or almost unrealizable. Then, some projects are lost-competition entries, because obviously, we know a lot about—because we started this conversation with architecture—architects published their unrealized projects. A long time before some of these buildings Frank Gehry did could actually be realized they were unrealized projects.

SB: They called it “paper architecture,” right?

HUO: Yeah, exactly. I think it’s published and then often, through that, reality is produced. I think, with artists, we know very little about artists’ or poets’ or novelists’ unrealized projects. I find it always very interesting to ask that question. Some projects can also be censored. Doris Lessing always told me, “There are also the projects we want to do but don’t dare to do.” I always had this dream of writing a novel, but I just always thought it probably would be really embarrassing, so I’ve just simply not dared to do it.

SB: [Laughs]

HUO: That’s what Doris Lessing called a “self-censored” project. So, within this whole range of the unbuilt or the unrealized, it’s always the main focus of my conversations. Very often, I try to enable these projects to happen. In that sense, it’s an important part, I think, of the conversation project.

The fact that today it exists as an archive of almost four thousand hours is really thanks to Jonas Mekas, because when I was very young, in my early twenties, because already as a teenager, I visited artists. I had these train tickets and went all over Europe to visit artists by night train. Then Jonas Mekas, at this moment when I was maybe 20 or 21, he said, “You will one day regret it if you don’t have these conversations recorded, because you might not remember everything.” We were sitting in a café in Paris, and he was there with this camera filming me whilst he was actually telling me that.

SB: [Laughs]

HUO: Then I said, “But I’m a little bit too shy to do that.” He said, “You don’t really have to be… This doesn’t have to be professional equipment because it’s really intimidating, professional equipment. It doesn’t matter if the camera falls on the floor, or if it falls from the tripod or… The more improvised it is, the better it is, because it’s relaxed.” Then he said something else that was really interesting. He said, “Don’t do only sound. You should also film it.” So then I went to a shop, bought a little video camera. I don’t film everything, but about half of it is filmed. It really exists thanks to Jonas.

Also, Jonas gave me another [piece of] advice. He gave me the advice to be incredibly paranoid about losing archives. He basically said, “We need to always keep many copies.” [Laughter] There were many hard drives because you can’t trust the cloud, because if there is a problem with the data center… The other day, somewhere in France, a data center burned down, and actually, a lot of people lost, literally, all their data. What Jonas Mekas said in 1991, when he said that we need to somehow be paranoid about losing data, that’s something I also took to heart.

SB: Yeah, it makes me think of, there’s the sound artist Bernie Krause, who went around getting field recordings of rare species of animals and birds all over the world, and had this incredible archive of sound. And then, there was a wildfire in California, it burned his house down, and all of his original recordings disappeared. But I believe it was the year before—I think thanks to Cartier Foundation, actually—all of it had been archived digitally. So, this incredible archive of sound of species, many of which no longer exist, would be totally gone had he not had it archived.

HUO: Yeah, it’s a really beautiful work, and it’s, at the moment, exhibited in the new Cartier Foundation in Paris [via the “Être Nature” section of the permanent collection exhibition]. Actually, the Soundwalk Collective has made an installation with the archive.

SB: Oh, great.

HUO: And yeah, it’s incredible. It’s saved because of that. It could have been lost.

SB: Yeah. Well, one of the things about your conversations, too, that I wanted to bring up has to do with age, because you’ve made this long effort to capture octogenarians, nonagenarians, centenarians… I imagine, obviously, this is for their wisdom; these are people who have lived many lives, but also, for posterity. It is a record of their words and their thinking. How do you see it?

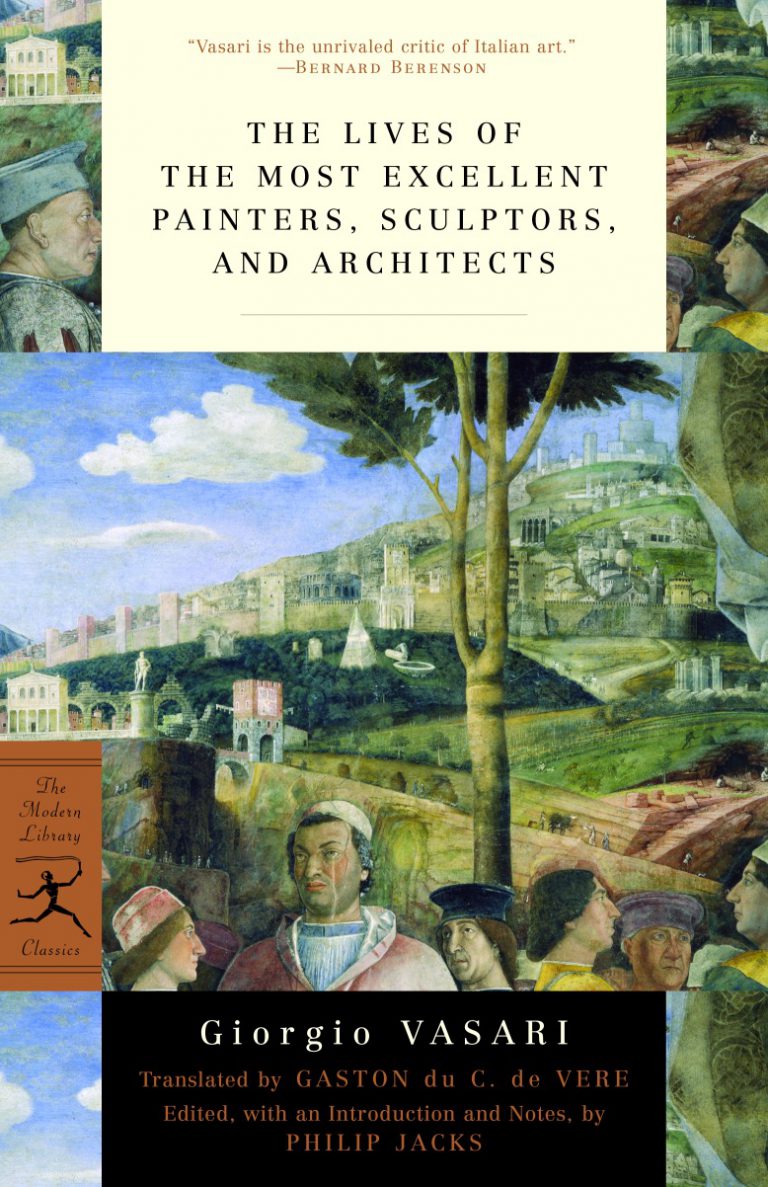

HUO: Yeah, growing up in Switzerland as a teenager, I read [Giorgio] Vasari’s The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. I think that the reading of this book was probably the most important book of my adolescence, because I read it, and then I thought there might actually be some historic figures in our time like Vasari wrote about, and maybe we should look at their work. Then I started to look at a lot of magazines and books. It was the eighties. I was a teenager in the eighties, so there wasn’t the internet. I had to go to libraries.

Then there was this very strange house, an abandoned house in a park. Because I grew up in a small town, Weinfelden. Maybe nine thousand people lived there. So, the town didn’t really have a lyceum. Would that be a high school, or what is it?

SB: Yeah, I guess so, a school.

HUO: Yeah. I didn’t have a lyceum, a school. We always had to take the train in the morning and go to Kreuzlingen and Konstanz, which is, basically, twenty miles away, fifteen, twenty miles away. We had to, basically, go to school there, which was very interesting, because it was basically the border town between Switzerland and Germany, and next door there was also Austria. This idea of crossing frontiers, crossing boundaries, going from one country to the next became a daily practice, because, as kids we would basically go for lunch to Germany, or we’d always go to the movies in Germany. Every day, we, several times, crossed the border.

This abandoned house really felt haunted. I asked my teacher [about it] one day, and the teacher said that it’s actually the former clinic of professor [Ludwig] Binswanger, the famous psychologist who, basically, was the theme of Foucault’s thesis. But it’s also the clinic where Aby Warburg was treated and famously wrote his “[A Lecture on] Serpent Ritual.” Actually, the first time this important text was presented was in a lecture to the other patients at the end of his stay there.

The teacher told me all these stories, and it sounded incredible. So I went to the library. In a way, Aby Warburg became a super important inspiration, because I read about these artists. I was too young to fully understand it, but I understood that he had somehow created… Knowledge can also be produced through unexpected encounters.

So, with my pocket money, as a teenager, I started to buy these postcards, and I started to make these arrangements on cardboard, and then, a little bit later on, I started to put them in boxes and started to make my own museum.

Then a second, I would say, revelation happened, because I read about an exhibition of Claude Sandoz. The Swiss railway system—again, it’s the analog age, it’s the time where there were landlines. It’s also a time where there was a train timetable, which arrived, always, in January. It was a very thick book about every single train in Switzerland and every train connection, and also, the train connections from Switzerland to other countries. I started to plot fictitious journeys.

SB: [Laughs]

HUO: I was very inspired by Robert Walser, because Robert Walser was my childhood hero, and I read all his books. Obviously, after his exile in Berlin, he went on a fictitious exile to Paris, and then, he went on an interior exile in Switzerland, when he went on these walks. So I started to plan fictitious journeys already when I was 12, 13, 14, always looking at this book, where I could go.

I also started to, at school, passionately learn languages. I learned Spanish, and also Italian and French and English, because I wanted to get ready to leave—which, I think when you grow up in a very small country, it’s important, this idea that one prepares. There isn’t a big city in Switzerland. I needed to be ready to move to a bigger city.

Then, on the cover of the railways book, on the timetable, there was always an artwork. I think that’s also curatorially something which is important for me up to today, which is this idea that art can appear where we expect it least, that it doesn’t just happen behind the doors of galleries and museums, but it actually goes as public art or through dissemination throughout society.

SB: Yeah, some of your earliest curatorial projects: your kitchen [“The Kitchen Show” in St. Gallen, Switzerland in 1991]; a hotel room [“Hotel Carlton Palace / Chambre 763” in Paris in 1993]; the sewer museum in, where was it, Austria [“Cloaca Maxima” at the Museum der Stadtentwässerung in Zürich, in 1994]?

HUO: Yeah, exhibitions in unexpected locations. I think, very often, I’ve been interested in—and still am—in this idea that we basically bring art to people who might otherwise not go to museums. Because I grew up in a house where my parents wouldn’t go to museums. I would never have discovered the portal of art if art wouldn’t have come to me through posters Keith Haring would do for the Montreux Jazz Festival; through the street art of the sprayer of Zürich, the legendary Harald Naegeli; or through the artworks of the outsider artist Hans Krüsi, a very famous art brut artist. Who, in the eighties, when I was a teen, he would basically be in Zürich, and he was a migrant worker who worked on farms, and he, like Andy Warhol, recorded everything. So he recorded all the animal voices and he recorded the sounds of the farm. But then he made lots of drawings of cows, and he also wanted to do cinema, but he didn’t have a camera. So he basically created these infinite cow drawings and created cow machines.

SB: [Laughs]

HUO: This guy basically sold flowers at the Bahnhofstrasse in Zürich, and my parents would sometimes go there on a weekend. We would basically see this outsider artist, not only selling flowers, but selling little drawings of cows. In a way, art came to me through that.

Then through the cover of this timetable. Then I read that the artist Claude Sandoz, who had actually done the cover, had an exhibition. So I went to see it. I was 16. I really liked it. That’s when I for the first time realized one could actually meet—not only, as Vasari said, there are great artists, but I could actually meet him. So I wrote him a letter and asked for a studio visit. That then became, in a way, a chain reaction, because soon after that I was in the studio of Fischli Weiss and then everything kind of unfolded from there.

SB: [Gerhard] Richter, [Alighiero] Boetti—it just unfolded.

HUO: Yeah. To come back to your question about the archive: At the beginning, it was never really this idea of a master plan of doing this big archive. It’s a serendipity, in a way. It sort of just happened.

SB: And back to your crossing borders thing, too, right? It was just a series of encounters that led from one studio to the next, in a way. Could you also talk—just taking more of a thirty-thousand-foot view, let’s say—when you think about the vast relationship between art and time, what comes to mind for you?

HUO: Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno once created an association to liberate time. I think that art can be a portal to liberate time. I’ve always also thought that there are so many different ways to work with time differently, so that it’s not a sort of a homogenized schedule where we have to fit in, but that we can actually think about time in different ways. The Brutally Early Club is one example of that, but I think there are many more, in a way, to just use time differently.

I was thinking, actually, when I wrote Life in Progress, this more autobiographical book, last year, I was thinking that maybe it has to do also with my accident when I was 6.

I was involved in this car accident. It was many weeks between life and death. I think, at that time, something really profound happened. I suddenly became aware, not only of mortality, but also how precious every day is, and that maybe we never know how many more days there are, that we need to make the best out of every day and that we need to get it all done. A lot grew out of that in my relation to time.

SB: It makes me think, you’ve said that you were effectively reborn in Fischli Weiss’s studio, but I also think you were perhaps also reborn in a way in that moment because going through something like that does shift your relationship with time in an instant.

HUO: Yeah, I think totally it was a completely new life started after that because also, because I couldn’t do sports and I was in hospital for a long time. My relationship to books also began there.

SB: And perhaps urgency? I think about this notion of what you’ve said. If we’re talking about urgency, we have to talk about time. You’ve even organized an exhibition called “It’s Urgent!” Your favorite word is urgent, I would say. Could you maybe speak a little bit about this relationship between trauma or your experience and urgency?

HUO: Yeah. Through the accident what happened is the urgency to just do things and not to wait. But I think it’s about working very much with different temporalities. Because sometimes I think it’s important that we don’t plan things too long in advance, that things can be improvised, that things can be instantaneous, that things can be spontaneous. Particularly with exhibitions, very often if you plan with a checklist years in advance, by the time the exhibition happens, it’s basically very static, so I think the idea that we bring in something…

That brings us then, also, to architecture, because I think a big inspiration, I think, came from other fields for me. A lot of my work really changed through encounters with poets like Etel Adnan, it changed through encounters with poets and writers like Édouard Glissant, and it changed through encounters with architects. And an architect, actually, of the same generation as Gehry was Yona Friedman. I met Yona also when I was very young, at the beginning of my trajectory, and he explained to me that he doesn’t really believe in this idea of a top-down master plan in urbanism, that he believes in this idea that we need to have spontaneous moments, because we never really know what people are going to do in a city. He was showing me: “We can’t know if the person now will turn left or right.” There’s a big unpredictability. He was talking about this idea, and then he was sort of mirroring it back at my profession. He was basically saying that, “You’re a curator with your checklist and your master plans. You should try to question that.” That opened, again, a whole new chapter. I started to think, How could I bring in self-organization, spontaneity into my shows?

But that doesn’t mean that it’s all related to urgency or speed, because sometimes I believe [that] to not work with time in a homogenous way means that we can also go from the extremely fast to the extremely slow. Fernand Braudel’s longue durée was always also a very important thing for me, this idea that we can work on a project— Because I felt quite… After “The Kitchen Show,” because I did this exhibition in my kitchen, which had, over three months, twenty-seven visitors, had a budget of three hundred dollars.

SB: [Laughs]

HUO: It was very D.I.Y. One of the visitors was the curator Jean de Loisy, of the Cartier Foundation. He actually came to St. Gallen because Fischli Weiss had sent him to “The Kitchen Show.” He was one of the few people from outside Switzerland who saw that show. I said, basically, I had the car—I often borrowed this very old Volvo from my father and my mother. I said I can bring him to the airport, but then I forgot actually to put fuel into the car, so then we stopped in the middle of the highway. Then we had this long conversation because he missed his flight. Through that—we had a wonderful conversation—I got invited to this grant at the Cartier Foundation with him and Marie-Claude Beaud. That was another life-changing kind of moment.

SB: Wait, I just love this, though: You basically got invited to the Cartier Foundation because of this conversation as a result of not having enough fuel in the car.

HUO: Yeah.

SB: How amazing. [Laughs]

HUO: But then also, this was a great experience, because the Cartier Foundation, it was very interdisciplinary early on because of Marie-Claude Beaud. One evening, there would be a philosopher; another evening, a fashion designer. For the early nineties, that was very unusual in the art world. It was really another big opening for me.

But that car I borrowed from my parents had another really important function at some point, because I had just made my driver’s license and, as you mentioned, Fischli Weiss were my mentors and close friends. They obviously did this extraordinary artwork of the snowman [“Snowman” (1989–90)], the snowman which never melts. And it’s now at the Beyeler Fondation, in Basel, in Riehen, and it’s actually with solar panels. So it’s not a waste of energy; it’s fueled by solar energy. But it never melts. It’s an eternal snowman. But this work in the eighties was originally commissioned for a power plant in Germany.

Basically, Kasper König, who was then the most well-known impresario and exhibition-maker, was the curator, and Fischli Weiss was basically meant to make a proposal. They were late with the proposal, and it was Thursday afternoon and the dummy for the snowman—made it in polyurethane—had to be in Saarbrücken on Friday morning. There was just no way any kind of courier service could bring it, and they couldn’t do it.

So they rang me and they said, “Don’t you have some time…?” They knew that I just got my driver’s license. They said, “Could you borrow the car of your parents and drive this dummy, this maquette of the snowman to Saarbrücken?” So I said, “Absolutely.” I took the car, went to Zürich.

SB: [Laughs]

HUO: They put the dummy of the snowman on the passenger seat with a safety belt, and then I drove all night to Saarbrücken. I arrived at 6 a.m., had the coffee, and then at 7 a.m., the legendary Kasper König showed up on the bridge. I’ll never forget this. I handed him over [the “Snowman” dummy], and he obviously had appreciated the effort of driving all night long, so he invited me for breakfast. That’s how I then started to work with him. That’s how I got my first job. So both—

SB: The Volvo! [Laughs] Very important. How incredible.

Well, in researching for this episode, one of my favorite time references is from your book Life in Progress, which was recently published in the U.K. and will come out in the U.S. next spring. In it, you write about your schoolteacher mother, who had placed stickers all over her apartment with these different messages, aphorisms, or quotes. You weren’t quite sure where they came from. But her favorite was, “Time lingers, time rushes, time divides, and time heals.” I just love that. [Laughs]

HUO: Yeah, thank you. Actually, it was fascinating, because when I began to travel a lot at the beginning, my parents were really worried. When I was like 16, 17, I traveled all over Europe. So often they kind of traveled, they tried to travel with me. Obviously, this became kind of complicated, because I would always travel by night train. So it was too tiresome for them. They also had to work. Ultimately, they would just basically accept the fact that I had to travel alone and all of that. But then I obviously was aware that they were very worried.

I read Serge Daney—who was always a big inspiration, the film critic—and he said that he would always send every day a postcard to the parents, that that would somehow be reassuring. So I started that as well. I would always send a postcard, but I would also always send my parents everything I would do. If I did a lecture, I would send them the invitation card. If I would write a text for a magazine, I would send them the magazine. At the beginning, most of my texts were kind of smaller contributions to big anthologies. For the first couple of years, I didn’t do my own books, but I would send my parents the whole book. What I didn’t know initially is that my mother would really read the whole thing. If there was an anthology of a thousand pages and I would have one page, she would read all the nine hundred ninety-nine other pages, as well. If I would write the little text for the Venice Biennale, she would read the entire thing. That went on for many, many years.

Then, when my mother turned 80, she actually started her own art practice. She started to make objects and would sort of hide them in the apartment so that they would sort of be visible and invisible. It became a whole kind of exhibition.

SB: It’s incredible, too, that in that sense, you were her portal into the world of art. This traveling on the train was also giving her access to a world she never had before.

HUO: Yeah, that’s kind of what happened, yeah.

SB: Wow. Bringing up your mother, one of the things that really moved me in your book was that—and this was Rosemarie Trockel, I believe, who had told you, “Make sure you have conversations with her before she passes.” So you went, and she was old and ill at that point, and you went and had these conversations. What was that like for you?

HUO: Yeah. Rosemarie gave me a lot of advice, also. What happened is, because I was so young—I was like 16, 17, and I would show up in these studios—the artists kind of all felt they had to somehow give me advice or tasks, because I just knew that I was really passionate about art. I didn’t know exactly what I one day wanted to do. Many of the artists felt that they somehow had to… It was almost like a mentor relationship, and they gave me ideas and actually many of them gave me tasks.

Alighiero Boetti would give me the task to basically ask artists about the unrealized projects. That came from him. Fischli Weiss gave me another task—that was quite at the beginning. They basically said… In Switzerland, there’s a lot of art from all over the world because there’s Art Basel. They said, “You should actually go to Basel for two days and look at every single artwork at the fair, take notes, and then tell us what you liked.” So it was a good exercise.

They all would give me tasks. Rosemarie gave me a very interesting task also, which I continue until today, because she basically said that—I was like 16, 17, and she was 33. She said it’s fantastic that I would visit a young artist like her, and I should always continue to do that, because young artists need support. But I should be aware, she said, that there are many extraordinary artists from previous generations who don’t have the visibility they deserve. She was particularly emphasizing female artists who had been working for a long, long time. It was just the beginning that Louise Bourgeois started to be well known in Europe. She had her first museum which was in the early eighties in New York. And then in the mid-eighties, it started in Europe, very late in her life.

Rosemarie said, “This is wonderful, but there are many other artists who basically should have that visibility.” She said, “Just ask that question when you meet young artists: ‘Who inspires you?’”

I took a night train from Cologne. I went to Vienna; the train arrived. I went to see a group of young artists in the RIVA Studio, and I asked them that question. They all immediately said, “It’s absolutely the Louise Bourgeois, basically, of Vienna is Maria Lassnig.” Who at that time wasn’t known at all outside Austria and Germany. She was an extraordinary painter, filmmaker, and animator who lived for many, many years in New York and did incredible work here. I rang up Maria Lassnig, and I went to see her.

Until today—for example, for us at the Serpentine—at least once a year, we have an exhibition which has to do with that. The series is called “A Protest Against Forgetting.” Basically, extraordinary artists—for example, this year, Arpita Singh, who is an artist in her late eighties from India, who is very well known in India, inspires many young artists, but it [“Arpita Singh: Remembering”] was her first museum show in Europe.

The same happened with Kamala Ibrahim Ishaq, an extraordinarily influential painter, one of the most influential painters from Africa. We did her first retrospective [“States of Oneness”]. Years earlier, of course, ten years or longer before, it would be the same with Etel Adnan [“The Weight of the World,” in 2016] or Faith Ringgold [in 2019], when we did the first kind of bigger museum show of “Faith in Europe.” In a way, it’s not only that artists when I was a teen gave me these tasks, but very often, actually, in many cases, I continue them until today.

SB: You still have mentors.

HUO: Yeah, every day.

SB: [Laughs] I love that. Maybe just speak a little bit, or just go back to this time with your mother, too, because I think it’s amazing that you have this thing you do—these conversations with artists—and then to have the conversation with your mother, how incredible.

HUO: Yeah. It was basically Rosemarie’s idea because she says that it has also to do with the fact that she said that we might… When somebody passes away, we then, at a certain moment, years later, don’t remember so much the voice. It’s important that you have this possibility to listen to it again. The conversations were very far-reaching. She told me through these conversations many things I had simply not heard before, about the family, about her parents, about my father. Many, many stories.

SB: I want to bring up the Serpentine. I can’t believe we’ve barely touched on it. But this incredible… I don’t know what to even classify the Serpentine as, because it’s not a museum. It’s many things. It’s a sort of cabinet. It’s this incredible vessel within Hyde Park in London. And you’ve been there since 2006, so nearly twenty years at this point. Tell me about your time there. How would you classify your “Serpentine time?” How do you think about this period?

HUO: Yeah, the Serpentine time is exciting and it really grew out of the Paris time, because I mean we’ve mostly spoken about the beginnings of—

SB: Yes.

HUO: At a certain moment, I basically had this grant in Paris, and then, through that, got a job at the Musée d’Art Moderne [de Paris] and became the migratory curator there. It was basically a new job they created for me. My role was to migrate and bring ideas from outside into the museum and do exhibitions in the museum, which happened in unexpected locations in the museum. A migratory program, so as to say, that was with Suzanne Pagé. I did that for many years at the museum and, at a certain moment, I felt, around 2000, that I wanted to do more at the Musée d’Art Moderne because I felt, as an independent curator, one would always do group shows. I felt it would be really interesting to go deeper with artists.

I think, in a way, it’s a very deep working relationship one can have with an artist when one really works for a year or two on a monographic solo show and can just deepen this dialogue. It felt the time for that had come. That is really something which then I took more institutional responsibility in Paris. That then led, in 2006, to the invitation that Julia Peyton-Jones invited me to join her at the Serpentine. I would say there were many reasons for that. I felt that the Serpentine’s park connection was so exciting. I’ve always felt that museums and institutions in a park are magical. The same is true for the Beyeler. I’ve always been also very fond of the Louisiana Museum [in Humlebaek, Denmark]. I love that museum.

SB: Mm-hmm.

HUO: It somehow connects to parks, to nature; at the Louisiana Museum, it’s the sea.

Then I would say the idea, also, that [the Serpentine] is not a huge building; it’s a former teahouse, so the artists can take it over and create a Gesamtkunstwerk. There is nothing else to distract from it, right? It’s basically a takeover when an artist does a show there. And the blurring between inside and the outside I’ve always found very interesting. This year, our CEO, Bettina Korek, and I and our teams did an exhibition with Giuseppe Penone, and it was basically the trees in the park and then his trees he brought and then the park came into the building and you had the scent of the leaves inside the gallery.

Penone said something very interesting. He said he really wanted to connect the outside and inside because he loves the fact that people just walk in, and there isn’t really a threshold because it’s free admission. To go back to this idea of how art came to me when I was a teenager, not from a family who had access to art; it happened because of free admission. It happened because I didn’t have to basically pay a ticket to see the street art of Hart Negele; or the little drawings of Hans Krüsi, who sold flowers; or the artwork on the cover of the timetable. I suddenly thought, Wow, the Serpentine is actually like that. It’s a museum, it’s an institution, it’s a kunsthalle, but it has free admission. It’s like the park. It’s like a common. People can just come inside. Very often people also don’t even know what is inside. They’re just curious. And then suddenly they get hooked and get into art.

Some years ago, a taxi driver dropped me off. I came back from a trip really early and I went to the office at 7, and obviously the taxi driver thought, at 7, it’s not opening hours, so this person probably works there. He asked me if I worked there; I said yes. He said that he always wanted to talk to someone who works at the Serpentine because he wanted to tell the story of his daughter, because they came on a walk on a Sunday and all of a sudden the daughter ran into the pavilion and basically had a revelation, and now studies architecture. He wanted to thank us, and he wanted to thank us particularly because he said she would never have seen it because he always told his kids, “Museums are not for people like us.” She grew up basically in a household, again, where there wasn’t art. So, because we do these pavilions outside the gallery, and they never have doors, people can just walk in, they can stumble across it. I believe in this idea that art and architecture can transform us, and can create these extraordinary experiences, which I think is why I get out of bed in the morning, to enable people to have this experience or to make these experiences possible for people.

So I was excited about that with the Serpentine, that it has this free admission. I was also excited about the architectural dimension because obviously coming from Vasari, for me art and architecture was never really separated in that sense. I always had that book, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. But in Paris at the Musée d’Art Moderne, I couldn’t really do architecture. I remember we had lots of discussions in Paris about exhibiting architecture, and yes, I could have done a show of architecture there, but I always felt like to exhibit marquettes of architecture or drawings is not the real deal. When you show art, you don’t show documentation of art; you show the art. So then I thought, if you show architecture, you need to show the architecture. I was always super obsessed by the Barcelona Pavilion to come back to that. I was thinking the project which Julia [Peyton-Jones] started with Zaha Hadid in 2000—

SB: The Serpentine Pavilion.

HUO: Yeah, commissioning a pavilion every year. It’s this incredible thing that an institution can be a client for architecture every year. That was definitely one of the main reasons I got so excited.

Then, of course, London as a city. I was already, in the nineties when I was in Paris, I did a big show on the London art scene. That was the first time I sort of tried to do an exhibition between organization and self-organization, because we did this show “Life/Live” [in 1996]. We basically, at the Museum in Paris, brought in these amazing artist-run spaces from the nineties—City Racing, Transmission from Glasgow, others from different cities. They would self-organize their show; our show would be a bridge between all these self-organized entities. So I had already spent a lot of time in London, then, for research.

The pavilion became very exciting, because we continued for several years what Julia had started—and the rule of the game was always the same, that it’s the first building of an architect in the U.K., so that it brings in new voices. Even if London is an incredibly international city for architecture, and even if London has these extraordinary architects—it has produced amazing generations of architects, as we know—not many architects from abroad had actually built there.

And there were so many projects which never happened. A lot of international architects just didn’t get to build there. So we could basically do the first building of [Kazuyo] Sejima and SANAA, [Ryue] Nishizawa, the first building of Gehry, of [Oscar] Niemeyer, of all these architects in the U.K. And then after about, I would say, twelve years—I mean twelve years into the scheme, six years into my time in London, around 2012—I remember we started to think, first of all, we’ve worked with most of the really legendary architects who had not built in the U.K., but we also saw a new generation of architects emerging. We also realized that the scheme had become quite well known and established, because we always wanted to do something which is not—it’s not like an art institution doing something by bringing in architecture, but it’s something which had to matter for the architecture world.

The pavilion started to be really well known, not only in the art world, but also in the architecture world, so we thought very practically we could actually use this to basically enable younger architects to have more visibility and do similar things we do with exhibitions, where very often we would do the first museum show, the first institutional show for younger artists, and do that with architects. The first younger architect we did this with was Sou Fujimoto, and it’s been going on ever since. We hope that it’s useful. I always think that’s a key question with projects also, how useful they can be for the world. It’s such an important moment in architecture for the architecture world to be more polyphonic, more diverse, and very importantly also that there is just more visibility for female architects.

That’s something which, over the last couple of years—we were very happy to have worked early on with Frida Escobedo before she had really worked outside Mexico. I had seen an amazing… She had mostly done installations, also internationally. She had done this amazing installation [Civic Stage] for the design biennial in Lisbon, this disk. And I remember I passed by that one evening and so many people had used it in different ways. I said, “This totally reminds me of Serpentine, this idea of it being for everyone.” So we invited Frida, and Frida soon after won the competition for the Met and now the Pompidou and—

SB: She designed the building we’re sitting in.

HUO: Which is kind of amazing. [Laughter] And then the same with Lina Ghotmeh.

SB: Who’s been a guest on the show, actually.

HUO: Exactly—I saw that—and who’s now doing the British Museum and the first new pavilion in the Giardini [in Venice] since South Korea, which is going to be the Qatar pavilion. Then of course also Sumayya Vally, who’s been the youngest architect we’ve actually featured, who now has this important bridge project in Belgium and also works all over the world.

This year, we were very, very delighted to work with Marina Tabassum, who has done fundamentally important work in Bangladesh—basically, places for gathering, but also architecture addressing the climate emergency, with her Khudi Bari project—but had not really built outside Bangladesh and, for us, is really one of the most important architects of the twenty-first century.

SB: Well, yeah, what you’re saying is so incredible, because you were working with, as you said, the Zaha and Frank Gehry and Peter Zumthor and these legendary names, and then it sort of evolved into this platform for more emerging talent. What’s interesting, I think, is that in architecture, until the Serpentine Pavilion, I don’t know that there was such a— Back to time, it happens every year, there’s a sort of ritual to it, it’s recurring. It’s interesting to me that architecture, as one of the slowest arts, has this platform that allows a dialogue to occur in time that otherwise wouldn’t really occur without it. I’m curious to hear your take on that because, to me, it is interesting how—just to use Frida Escobedo and Lina Ghotmeh as examples—they were already on a certain upward trajectory, but this platform really gave them another spark. It gave them another opportunity to showcase their thinking in real time.

HUO: Yeah. I think it’s got to do with the fact that maybe it’s an experience, because one can actually experience a building of theirs. And it happens in a very central location where a lot of people see it. I think it has also got to do with that. It’s hundreds of thousands of people who visit the Serpentine Pavilion. In that sense, it has probably more visibility than a lot of other commissions an architect could do, which maybe are bigger. Even if it’s small, it is very, very visible. And I think also pavilions allow experimentation because there are of course a couple of… There’s a brief and it needs to function within the brief, but a pavilion has a lot of freedom because it’s not a permanent building.

One of the things which is in our brief is that it needs to be repositioned later on. It always has to have a second life, because otherwise it’s not sustainable. So each single pavilion goes on somewhere.

SB: Right. Frank Gehry is now [at Château La Coste] in the south of France.

HUO: Yes. And then the Sou Fujimoto, the first younger architect we did, is on the Central Square in Tirana. It belongs to the Luma Foundation and is now in Tirana. Smiljan Radic is in Somerset at Hauser and Wirth. The Bjarke Ingels is in Canada. Many of these pavilions develop second life. And we have a couple of exciting announcements coming up for next year because next year…

SB: Oh, good.

HUO: So next year is the twenty-fifth pavilion. This year was the twenty-fifth year, but next year is the twenty-fifth pavilion, and there will be some exciting announcements of some pavilions from the past which will reappear. Of course, also this year, for the first time, we also had a Play Pavilion. We had a second pavilion, actually, which is a Play Pavilion. And for Bettina Korek, our CEO, and for myself, our teams, what is really, really important, is also to foster new alliances with art institutions today. It’s not only to build bridges—many, many bridges—but also new alliances and unexpected partnerships, because obviously it’s important for a museum to work with other arts organizations, which is what we do, but it’s important to also work with organizations of a different kind. And so—

SB: Right. You just announced this big partnership with the FLAG organization. Could you share a little bit about that?

HUO: Yeah, we are very excited about this collaboration with the FLAG Art Foundation and Serpentine, where basically we’re going to have an art prize, which will lead to exhibitions of the artists who will win the award, both in London and in New York City. So that’s a new alliance.

Then, of course, the Play Pavilion was with the Lego Group, and there are so many people in the world who are interested in Legos, so that brought us a whole new audience. We commissioned Peter Cook, the co-founder of Archigram, to do this playpen. He’s always been interested in play.

Another example would be the collaboration we had with Acute and Fortnite, because obviously we also have a whole… That’s something which is, I think, another dimension, which is really key for us at the Serpentine, is this idea—and that goes back to your question from before. I was excited in 2006 to actually have this possibility for the first time to not only think about the exhibitions as a curator in a museum, but also, by assuming more responsibility, to think about how one can structurally change an art institution for the twenty-first century. That means, also, to kind of insert or introduce new departments. For example, we had—and continue to have—a whole focus on ecology. That began with Gustav Metzger, with the Extinction Marathon [in 2014], with a lot of projects we have. Until more recently, Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, who developed the [“Pollinator Pathmaker”] garden for us—the biggest artwork we’ve done in the park. It was a garden for pollinators. So, assisted by A.I., the designer and artist Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg developed a garden which really attracted an enormous amount of pollinators. It was not for us humans; it was for pollinators. And with A.I., Alexandra could basically determine which plants would work best for the pollinators. That would be a long-durational artwork, which would, in that sense, connect to the environment.

Of course, the other thing besides the ecology focus, which we introduced, is the experiments with technology. So with Serpentine Arts Technologies, it’s a whole department, and that means that we can actually produce video games, that we can work with projects related to A.I. over the last twelve years. But, of course, it is about fostering new alliances with new partners. So we did this exhibition with Fortnite, Acute, and KAWS, and the Serpentine North—the permanent Zaha Hadid building—was rebuilt virtually on the landing page of Fortnite. So we had, over two weeks, a hundred and fifty-two million visitors who saw this digitally and became acquainted or familiar with the Serpentine. That led to the fact that thousands and thousands of teenagers brought their parents to the physical exhibition, and usually it’s the other way around.

SB: Mmm. Well, I wanted to close our conversation with a long-view question here—and I know you like long-view questions. In your new book, you write, “This idea of a system with a longer time span is fundamental today for art in all its forms: We have to move beyond short-term thinking. We must think about objects that will last, contrary to the idea of fast fashion and design.” So I wanted to ask, do you see art, then, as an antidote to short-termism, in some ways? Does art help perpetuate ways of knowledge and thinking that eschew short-termism?

HUO: We always learn from artists. Basically, making studio visits all the time. I’ve realized over the last couple of years that more artists are interested in doing gardens, in doing farms. I mentioned Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, but there are many artists who have garden projects. But also the farming projects are really interesting. There is, of course, near New York, Dan Colen’s farm [Sky High Farm], but there’s also Otobong Nkanga and Yinka Shonibare. Both independently of each other, they have these art-farming projects in Nigeria. Adrián Villar Rojas just told me yesterday about the farm [Brick Farm] in Rosario, in Argentina. I don’t think that that’s true for all artists, but there is clearly a pattern there that more artists are interested in such long-durational projects. And I think at every moment in time, we should always think not only how can we bring art into the institution, but how does the institution have to change in order to accommodate where art goes? I just think it’s a very interesting challenge for the next couple of years to see how… With Alexandra, we’ve actually built the garden. With Yinka, we’ve done an exhibition where we showed Yinka’s different works, but then made a link to his farm in Nigeria. There was a whole room connecting to that. I do think that it’s something we need to think about. I would say that’s one pattern right now I see.

I think the other pattern that, in a way, connects is that we live in a world which is very divided, where a lot of people don’t talk to each other anymore, and I think exhibitions and art institutions are a great place where that can actually change, where we can bring people together. I think it’s one of the tasks today institutions have.

If you come right now to London, to the Serpentine, you can see two exhibitions. You can see the “House of Music” of Peter Doig. It brings together the world of music and the world of painting, the world of art. He creates a kind of a Gesamkunstwerk construct in the gallery. Peter Doig’s exhibition, it’s a whole display feature, with curtains and a new floor, but also chairs and tables—and paintings, of course, importantly, of Peter Doig. But then also sound systems, extraordinary speakers, which the world used to have in cinemas in the thirties and in the fifties, which have an amazing kind of analog. It’s very embodied analog sound quality. Then Peter’s record collections. But also a lot of guests. Lizzi Bougatsos is going to come soon. Brian Eno is going to come soon. They’re basically bringing records and playing their records, their vinyls. It’s kind of a celebration also of analog music. A lot of things happen because people actually talk to each other, because usually in a museum, people would go, maybe some friends or alone, but it’s quite rare that we talk to a stranger in a museum. Here, all of a sudden, people sit down at the table, they listen, they meet new people.

That’s also, of course, what happens with the Pavilion every year. Lina Ghotmeh called her pavilion “A Table!” Francis Kéré, who went on to win the Pritzker Prize, when he did the Serpentine Pavilion, he wanted the gathering place under a tree. Again, with Lina, it was the table; with Francis, it was the tree. With Theaster Gates, it was the Black Chapel—it was basically an extraordinary gathering place, where Theaster created a Black artist retreat. Again, gathering, again, coming together, bringing people together. Creating togetherness is, I think, what is so important now. Or with Minsuk Cho, it was actually an empty kind of Korean madang, which brought everything together. I think with Peter Doig, it’s an exhibition which tries to do that.

We also have a show by Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley called “The Delusion,” and it’s a video-game commission with a multiplayer immersive experience run on game engines. It really combines cooperative gaming and participatory theater. People can address topics of polarization, of social connection. Again, it leads to conversation. That is something which for Bettina, for me, for our teams, is really central, to enable that possibility for people to do so. And that is something we can see globally, I think, with a lot of artists right now, that there’s a desire to create, to bring things together, and so on.

I think another point, which is maybe quite central, and which is a pattern is… And that brings us to something we haven’t spoken about, which is one of my favorite topics, Édouard Glissant, because during my Paris years, I met Édouard and we started to spend a lot of time together. I would say, from him, I learned a lot—and it goes back also to your long-duration question—from him, I learned a lot about how, in the contemporary world, in the twenty-first century, we should somehow, working with exhibitions, working with museums, with art institutions, address the themes of globalization. Obviously, this is not the first time the world experiences globalization. There have been previous moments of globalization. But it’s certainly one of the most extreme moments of globalization, fueled by technology. Glissant always predicted that this will lead to homogenizing forces, the disappearance of languages, it will lead to the disappearance of cultural phenomena, languages disappearing at extreme speeds. But also handwriting.

It leads to my handwriting project, where I decided to basically dedicate my Instagram project to handwriting, because I felt that there was a risk that we don’t use handwriting anymore. Again, it was someone who gave me a task, because I was in the apartment of Umberto Eco, in Milano, and we did a conversation about archives. I always wanted Eco’s take on archives. At the end of the meeting, Umberto Eco had a key, a big key. It was a bit like in The Name of the Rose. I got a bit scared.

SB: [Laughs]

HUO: He took out this big key and he opened the door, and then led me to a secret room and locked the door behind us. And in this secret room, there were all these medieval, extremely old manuscripts, handwritten manuscripts. He had sort of got from monasteries. They were like time capsules. He was very, very special. He showed me this library of rare books, and he said, “I have this key because I don’t want anyone else to enter.” Then he opened the door again and said goodbye. We were in the stairway, and he said, “I am too old, but it’s your job. You have to save handwriting.” Then, I didn’t really know how to do that.

We were basically on vacation with my partner, Koo Jeong A, and also with Simone Fattal and Etel Adnan, the artists and poets. It was in Brittany, and it’s always raining, often raining during Christmastime, during the holidays in Brittany. It was December, and it was raining so strongly that we had to find shelter in a café. A few weeks earlier, Ryan Trecartin had downloaded the then-new app Instagram on my phone. I didn’t know what to do with it. We were in this café and had a long conversation, and at that moment—the rains would not stop. Then the inevitable happened, that Simone and Koo and I would go on our phones and answer some messages, but Etel didn’t have a smartphone, so she basically took out a notebook and then wrote the poem. That’s when it all came together, because then we realized: I just took a picture and I posted it.

In a way, this idea of what Glissant said, that homogenous globalization could make things disappear, but then, of course, Glissant understood early on, and that what makes him such a premonition—that there will be a counterreaction, that the opposite of globalization will lead to new localisms, to new nationalisms, to new lack of tolerance. He basically said that we need to resist both and find a sort of a mondialité, find a global dialogue which can listen, which can be aware of the dangers of globalization, but at the same time be tolerant, enable global dialogues. I really think about that every day. So I think that’s another pattern we can see.

I think in a way, we see a lot of art right now which thinks about this mondialité, in a Glissantian sense, and anyway, many of the other tool boxes Glissant gave us: archipelago, creolization, the right to opacity—there are so many. In all the conversations I had with him, I felt I learned so much. We can see, it’s amazing how many artists today relate to Édouard Glissant.

Then I would say another sort of—and, of course, to apply Glissant, because I apply it on a daily basis—leads also to longer-duration projects. For example, my “do it” project, which we did with Boltanski and Lavier, with Christian Boltanski and Bertrand Lavier, is a project made with instructions and recipes, and wherever it goes, it learns. It listens.

SB: More than thirty years old now!

HUO: Yeah, and it’s still happening. It’s basically very much also what Bernard Stiegler told me when he said, “How can we be local without being localist?” That’s what “do it” tries to be. It’s a project which basically is a long-duration, evolving learning system. I’ve always been interested in such projects. They can somehow become repertoire. Like in theater, it would be repertoire, but as opposed to repertoire, it’s always evolving. It’s always changing. In that sense, it does in an analog way what would happen with a video game digitally. Because so many artists are now working with video games. Also with technology, we can see that more and more artworks are becoming, somehow, like living organisms.

Then I would say a last point, where we can also see at the moment a pattern, is that more artists, I think, are interested in public art. Of course, that also has to do [with the fact] that certain artworks maybe can stay, that we can experience them for a longer time. There has been a lot of focus, I think, on exhibitions, but I think now I meet a lot of artists who are really interested—my partner, Koo Jeong A, started to do, some years ago these, skateboard-park sculptures, which are both sculptures, but they’re also phosphorescent skateparks that, actually, skaters can use at night. Once they’re installed, they stay for a very long time. So I think that’s something we can see.

A lot of artists right now also have projects of houses, which is interesting. I’ve always been interested in house museums. I did shows in the [Federico García] Lorca house [in Granada]; in the Barragan House; with Isabela Mora, in the house of Lina Bo Bardi. We usually spend a year in these houses developing exhibitions with artists. I find it very fascinating that, right now, a lot of artists are interested in developing these houses as kind of a Gesamkunsterk. I can then go back to Peter Doig’s “House of Music.” Somebody told me yesterday that there should be such a house of music, as Peter Doig did at the Serpentine, which will be there forever.

SB: Yeah. I also love that you’ve said, of curating, that curating exhibitions is “having slow lanes.” I almost feel like that’s what art does, too. Art is a portal into taking these different slow lanes, whether it’s wandering through a park and coming upon a public sculpture, or like your durational marathons are another example of what I would call a “slow lane,” where you just immerse yourself deeply in a world for a set period of time and then pop your head out again. [Laughs]

HUO: Yes, and maybe also, both in an analog way and in a digital way, it’s about the flâneur. It’s about the serendipity of most of my projects, where chance also is embraced. It’s often a controlled chance, but chance is embraced. I began with Robert Walser, and Robert Walser went on walks. I think this idea that we somehow need these moments of serendipity and of discovery and, particularly in a moment where more and more, there is this lock-in thing with the algorithm. We need to create analog and digital serendipity, and analog and digital “promenadology.”

It’s actually very beautiful that the Swiss landscape architect Lucius Burckhardt, who was a mentor of mine. He was also a mentor of [Jacques] Herzog [and Pierre] de Meuron. I should have mentioned that before, that actually at the same time and as a teenager of 16 to 17, when I started to visit artists, I met also, thanks to Bice Curiger, Jacques Herzog. She took me to the studio of Jacques Herzog.

SB: Oh, wow.

HUO: In a way, Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron planted the seed with architecture in me. Both Jacques and Pierre, and also I, were very inspired by Lucius Burckhardt. I curated the Swiss Pavilion for the Architecture Biennale some years ago, actually, celebrating two forgotten pioneers, Cedric Price and Lucius Burckhardt, through contemporary artists and architects. Lucius Burckhardt actually invented or defined a science at Kassel University called Promenadologie. I think in English it would be “strollology.” It’s the science of going on a stroll. I firmly believe that we need more strollology.

SB: Oh, man. What a great place to end. Well, I have one final question.

HUO: Actually, interestingly enough, yesterday we spoke with Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst, who are artists who work a lot with technology. We did this exhibition with them called “The Call,” which addressed real societal concerns with A.I., and platformed musical ensembles from all over the U.K. It basically looked at choirs as a coordination technology, and also, in a way, A.I.—the connection to A.I.—and they worked with different choirs all over the U.K. with a songbook, and created a data trust so that the choirs co-own it. It’s a kind of ethical use of A.I. Yesterday, Holly and Matt told me that with “vibe coding,” more and more coders actually code while strolling, so there might be vibe-coding strollology.

SB: [Laughs] All right, final question. This is maybe a cliché way of ending an interview with you. But I didn’t want to ask you the question you ask everyone, which is: Do you have any unfinished or unrealized projects? But what I did want to ask was, of all the answers you’ve ever gotten to that question, from everyone you’ve ever asked it to, what are some projects that have yet to be realized that you’d like to make happen, with an artist or an architect or otherwise?

HUO: Yeah. There is such an immense, basically a very big archive of answers, of course, in these four thousand hours.

SB: Overwhelming question, I know.

HUO: It’s a fascinating question because, in a way, I always wanted to do an exhibition and a book on all the answers I got for this question. It would be like a building full of unrealized projects, which would hopefully allow people to then realize these projects. Ironically, whenever we get close to realizing it, it falls through. This is why I never really have the mapping of the cartography, the Überblick, the overview, of all of them.

I do think that Cedric Price and Joan Littlewood had this wonderful project of the Fun Palace, which they told me about. Particularly Joan, a pioneer of street theater, sadly had passed away, but I did still meet Cedric. In my many conversations with Cedric, he explained to me this incredible idea of a big… It was, of course, an inspiration for Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano to do the Centre Georges-Pompidou. That was his idea of the Fun Palace, which was basically…

SB: Which, by the way, Frida [Escobedo] is now doing the project on. It’s so incredible.

HUO: Exactly. We were actually with Marta Minujín and Frida. I did a talk with Marta Minujín and Frida at Art Basel Paris. I hope it’s going to happen, because that’s an unrealized project I really hope is going to happen, because Frida and Marta, I asked them about the unrealized project at the end, and they came up with this idea to do, whilst the Pompidou is closed, a very big inflatabile. Marta Minujín does these public sculptures, inflated, where you can walk in. They’re very beautiful public art projects. It would be Frida and Marta doing a big Pompidou inflatable you can walk in while the Pompidou is closed. That came out of the talk.

No, but my real answer to your question is this Fun Palace, which is unrealized, where basically a theater performance can go into a lecture, a lecture can go into an opera, an opera can go into a concert, a concert can go into an exhibition, where you can have all these different functions, and where really all the disciplines can come together. I think, in a way, it’s been very difficult to realize that on the scale Cedric and Joan wanted to do it, because I think it would be incredibly expensive to plan it on that gigantic scale. But I think it is interesting, because the Serpentine Pavilions are, in that sense, mini Fun Palaces, because one day there is a film screening, one day they can go into a lecture. It can then transform into a performance, can transform into a dinner, can go into many, many things.

SB: It makes me think, too, of “Il Tempo del Postino,” this incredible time-based project you did.

HUO: Yeah. That was an opera we did with Philippe Parreno and twelve artists, where we basically gave the artists time, not space. That was part of the Manchester International Festival with Alex Poots. The idea was basically that it was an evening-filling program where every artist had approximately fifteen minutes, and they could work with an orchestra. It was a kind of a polyphonic opera done by visual artists.

Because the Fun Palace doesn’t exist, it took us a long time to find an institution where it could happen, because museums don’t have the space for that. In a way, it needed an opera space or a bigger theater space, and operas said, “That’s a museum show. We can’t do that.” Then, when the Manchester International Festival got invented, the festival could actually, as an interdisciplinary organization, make that happen.

In a way, we then also did this in A Prelude to The Shed with Alex, where we commissioned Kunlé Adeyemi, the architect, to do a small pavilion on an empty piece of land in New York City. This pavilion could actually open and close at all times. There would be a concert by Arca at night, and then just before there would be a choreography of Bill Forsythe, and then in the afternoon maybe a concert of opera, and then a conference, a scholarly conference, and things would just flow into each other. I think that was an example of that. But to actually really have it as an institution,as Cedric and Joan had imagined it, is kind of unrealized.

I would say another project which has always been on my mind, unrealized, is, of course—many artists have always mentioned this idea that we might need a new Black Mountain College, and, particularly at this point in time, this seems very important. There is actually a possibility now that such a new school can happen, because I’m working on this project with Laurene Powell Jobs and Abbye Churchill, at the former San Francisco Art Institute, because that building was basically saved by Laurene, who now wants it to be a school and a residency, really, for young artists. The idea there is to reflect upon what such an interdisciplinary school can be. Also, of course, it’s important, at this moment in time, thinking also about models, listening, because this is in a couple of years. We are listening to what artists think such a school should be—again, going back to listening, it’s listening sessions.

It’s interesting also to just look at models which have existed. For me, when I moved to Paris, I came there as a baby curator with this grant at the Cartier Foundation, and everywhere, everywhere I went, were the repercussions of this little school [Institut des hautes études en arts plastiques (IHEAP)] that Pontus Hultén, Daniel Buren, Sarkis, and Serge Fauchereau had done, which was basically a room, slightly bigger than this room, but not much bigger, with a table. They would basically have young artists from all over the world, and every week there would be an amazing talk and the artists, the young artists, would meet somebody.

What is really fascinating about this is also that the students not only did not have to pay, so it was free, but they were actually paid. Each young artist got a stipend to be part of that. It just seems to really be extremely urgent to think about such models now, because that produced a generation. It allowed artists who never would have had the possibility to have all these encounters, to grow. Not only did it produce basically my entire generation of artists, not only those who attended, but also their friends, because the— I don’t know what one would call this.

SB: Reverberations.

HUO: That’s the word! Thank you. The reverberations are so strong. Pierre Huyghe once told me that— He didn’t go to that school, but—the reverberations were so strong that he also felt deeply inspired by that. So, yeah, that’s definitely another important project. I think there need to be many such models. We need many such schools in the world. It’s interesting how many artists actually over the years have mentioned that.

Then I would say, in terms of the unrealized projects of artists, that there is also an amazing range of unrealized public art projects artists want to do. Because I think, very often, with public art projects, radical projects don’t necessarily win the competition. That’s why I really hope that we can one day make accessible the archive, because I think many of these projects should still somehow be realized.

SB: Well, Hans, thank you for coming, and I’m hopeful that many of the reverberations of this conversation will continue for those listening for a long time to come.

HUO: Thank you so much. It’s so wonderful to see you.

This interview was recorded in The Slowdown’s New York City studio on December 6, 2025. The transcript has been slightly condensed and edited for clarity. The episode was produced by Olivia Aylmer, Ramon Broza, Mimi Hannon, and Johnny Simon. Illustration by Paola Wiciak based on a photograph by Elias Hassos.